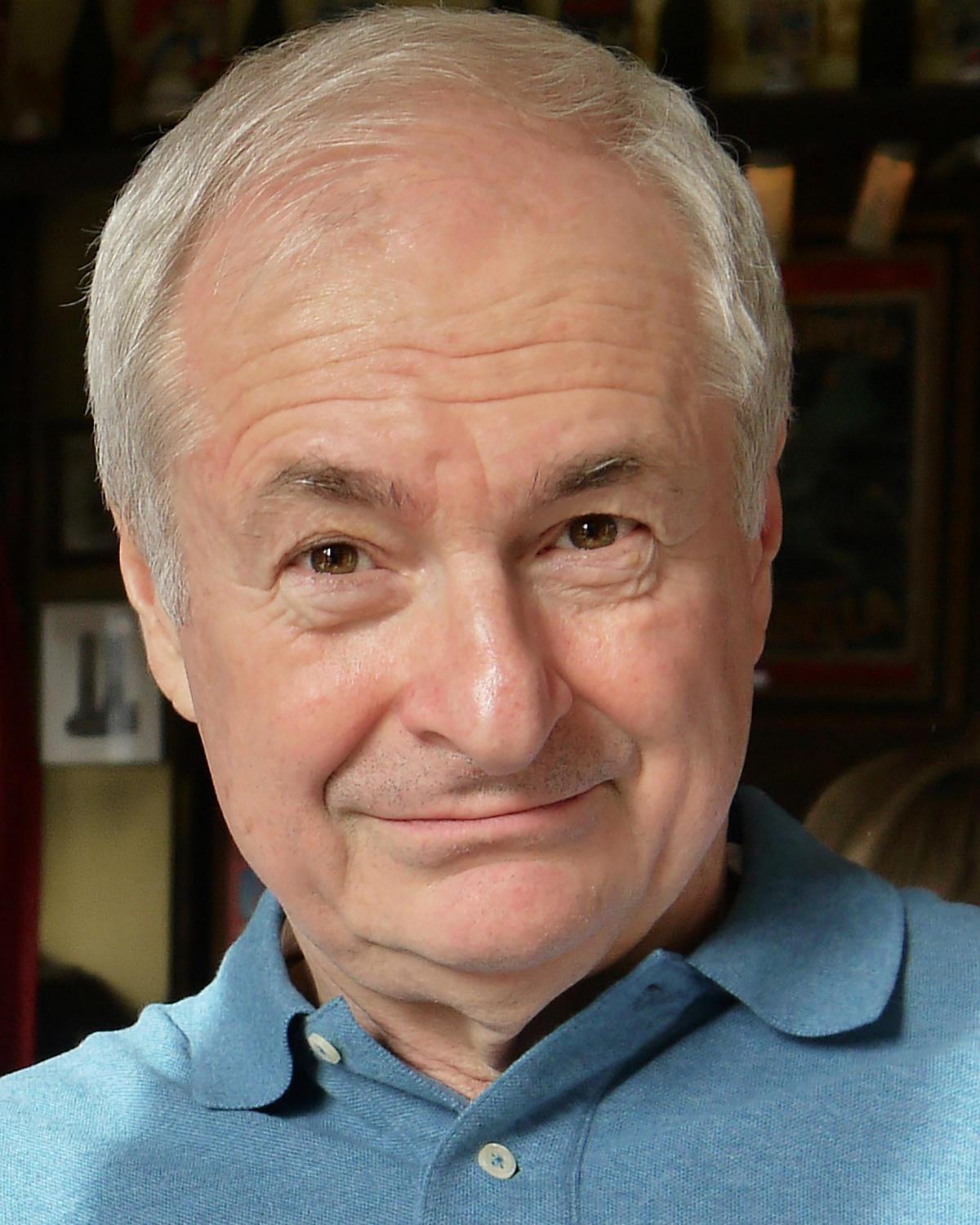

Radio broadcaster PAUL GAMBACCINI is bringing his first live show An Evening With The Great Gambo – The Professor of Pop to Dorset next month. He tells James Rampton what pop-pickers can expect.

Q: What gave you the terrific idea of performing your first ever live show, “An Evening With The Great Gambo – The Professor of Pop”?

A: It suddenly occurred to me that this autumn is the 45th anniversary of my joining Radio 1. I thought it was something I should take seriously and celebrate – this is my only life after all! Let’s just express gratitude for this career, which was inconceivable until I lived it. There’s never been a boy from America who has come over here and then worked for 45 years on national radio. When I was younger, I could never have imagined it, but here I am!

Q: Are you nervous about being on stage?

A: No. A few years ago, BBC2 and Channel 4 captioned me as “The Professor of Pop.” I was bemused at the time. That title was not something I’d ever thought of. But then I was made News International Visiting Professor of Broadcast Media at Oxford University. I had to do a string of lectures. That’s why I’m not afraid of being on stage during this tour.

Q: Are you looking forward to the buzz of live performing?

A: Definitely. I think connecting face-to-face with an audience will be really exciting. I’m fascinated to see the make-up of the audience because my career has been so diverse. I’ve done so many programmes about pop and classical music, not to mention my close encounter with the Metropolitan Police, the stupidest thing that has ever happened to me! Who knows what questions people will ask me in the show. I can’t wait!

Q: How did you get your big break in broadcasting in this country?

A: I read the Financial Times, and they have a weekly feature where they ask a public person which counts more: talent or ambition? For me, the most important thing has always been initiative. An example is when I attended a Bee Gees concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 1973 when I was writing for Rolling Stone magazine. I noticed that Elton John was also in the audience. He had just had a number one in the US, “Crocodile Rock”. As a result, he had become America’s biggest pop star without anyone really noticing – everyone at the time was obsessed with Stevie Wonder’s incredible run of albums. So I thought to myself, “It’s time for a lengthy Rolling Stone cover interview with Elton John.”

Q: What happened next?

A: So during the interval at the Bee Gees concert, I followed Elton into the men’s room. I asked him if he’d like to do a Rolling Stone cover interview. He politely told me to ask Helen Walters at his record label DJM, who took care of those things. I called her, and probably to Elton’s surprise, she said, “Great idea. Elton is about to go on tour in America, and this will be a very good way of promoting it.” She really liked the piece, and to thank me she took me to lunch with her husband, John Walters, who happened to be John Peel’s producer at Radio 1. He invited me to give a weekly talk on Radio 1, and that’s how my British radio career began. That was serendipity in action.

Q: While you modestly say that you are a “friendly acquaintance” of many popstars, your friendship with Elton John is much deeper. After that interview you became very good friends with him, didn’t you?

A: Yes. He’s one of my dear friends. We go back such a long way. He’s got such a great sense of humour. When I did that Rolling Stone interview with him in 1973, I said to him, “You’re so popular now that people invent awards to give you, don’t they?” He replied, “Yes. I just got an award in Germany for being the King of Pop. What’s next? The Queen of Lemonade?”

Q: Which modern popstars have you become friendly with?

A: I know Adele. I once went to give a lecture at the Brit School and I was worried because a girl in the front row was slouching throughout. I thought, “Am I that boring?” It turned out that the girl’s name was Miss Adkins, who emerged later as Adele.

Q: And then?

A: A few years later, I met her at the Ivor Novello Awards, which I was presenting. At the beginning, I said, “I’ll know how I’m doing when I look out at the audience to see if Miss Adkins is slouching or not!” When Adele came up to receive her award from Annie Lennox, the first thing she said was, “I’m so sorry if I gave the impression that I wasn’t interested when you gave that lecture at the Brit School, Paul. We were thrilled to have you there. My mum and I used to love listening to you. You were always a welcome visitor in our home.” I thought, “In her great moment of receiving the award, how generous of her to say that!”

Q: What do you particularly enjoy about radio broadcasting?

A: I love the one-to-one nature of communication on radio. The last ratings for Pick of the Pops on Radio 2 were 2.35 million people, but of course I never see them. People make a big deal about an artist selling out Wembley Stadium, but Wembley Stadium only holds 72,000 people – only! Every week on Pick of the Pops, we are doing 30 Wembley Stadiums. But while people on stage are communing with the crowd, we’re broadcasting one-to-one. You can only broadcast one-to-one. You can’t imagine broadcasting to a room of even eight different people. What’s really interesting is to ask yourself which one person you’re broadcasting to. In my case, it’s always the young me. I know what makes him happy and thrills him.

Q: What has been your biggest embarrassment as a broadcaster?

A: That happened on my first radio station at Dartmouth College. I went there because it had the largest college radio show in the US. It had an audience the size of BBC Radio London. Anyway, I went on air there, and I burped. There is no way of rationalising a burp. It’s there forever now and is part of history. Even though probably only a few thousand people heard it and it was 50 years ago, I still find myself apologising for it!

Q: Anything else?

A: I managed to avoid what would have been the biggest embarrassment of my career at Live Aid in 1985. I was broadcasting from Wembley Stadium when the feed to Bryan Adams in Philadelphia went down, and I had to fill the space. You’re literally broadcasting to the world. You’re ad-libbing and you don’t know how long for. Thank God I knew that Bryan Adams had co-written the Canadian equivalent of Band Aid, “Tears Are Not Enough”, so I was able to talk about that.

Q: How else did you fill the time?

A: I gave the details of how to donate to Live Aid and read out the American Express phone number to call. When the broadcaster finished, the director said, “That was very professional, Paul. The only problem is that Russia complained that you mentioned American Express.” That is surely the only time in history those words have been spoken! I was filling time, but trying to make it sound like I wasn’t filling time. Thank God, Adams was back on in 45 seconds. But it was the longest 45 seconds of my life!

Q: In “An Evening With The Great Gambo – The Professor of Pop”, you will also be discussing the impact on you of the Vietnam War, won’t you?

A: Yes. The turmoil of that era consumed my university years in the US. As more and more Americans were being required to serve, President Nixon instituted a lottery to decide who would be sent to Vietnam. They would pick birthdates at random to establish the order in which people would be called up. I was very lucky because my birthday was number 271, and in my year they only got up to 185.

Q: Did friends of yours end up being sent to Vietnam?

A: Yes. My tutorial partner in my first semester at Oxford was a man called Karl Marlantes. He went to Vietnam and established that he had killed at least 17 people - one of them, which was a nightmare for him, with his bare hands. When you’re going to war, it’s bad enough to think of dying. But how do you live with killing other people, especially when you don’t think of them as the enemy? Karl had to live with that experience.

Q: What became of Karl?

A: After four decades, he produced a novel entitled Matterhorn. When you have something that traumatic to process and you want to respond without rage and emotion, it takes time. Matterhorn is perhaps the novel of the Vietnam War, and at the age of 65 Karl became the oldest first novelist ever to enter the top 10 of the New York Times Bestsellers List. So I am someone who didn’t go to war, but whose life has been fundamentally touched by it.

Q: Why do you think the Vietnam War had such cataclysmic effect on your generation?

A: Because we had been brought up to believe we had saved the world, but the Vietnam War told my generation that the US could be wrong. The older generation thought, “It’s a war, we must be on the right side.” But we knew we were on the wrong side. It ripped us apart as a nation

Q: In addition, you will be talking about the impact of AIDS on your generation in “An Evening With The Great Gambo – The Professor of Pop”, won’t you?

A: Yes. One day in 1983, my best friend from Dartmouth, a Broadway actor called David Carroll, and I were attending a food festival on 8th Avenue in New York. A couple of friends came up and chatted to us. As we left, they said, “I guess we’ll see you at George’s funeral on Wednesday. He died from this new disease.”

Q: What took place then?

A: After they had gone, David said to me, “Will you excuse me for a moment? George was the man I loved most in the 1970s.” He retired to a side street to sit on a stoop and weep. At that moment I thought he was weeping for George. But I now know he was weeping for himself because he had just been told he was going to die, and he did. That was what it was like for us, magnified dozens of times.

Q: Are you delighted when you look back on this amazing career?

A: Absolutely. I managed to achieve my life goals in my 20s. When I applied to Dartmouth College in the US, I had to write an essay about what I wanted to accomplish in life. I wrote that I wanted to become a correspondent on an international showbiz magazine. I admired a journalist called Pete Martin from the Saturday Evening Post. He interviewed everyone from the radio icon Edward R. Murrow to Marilyn Monroe. I thought, “I want that” – and I got it!

Q: What other goals have you achieved?

A: For 41 years, I presented America’s Greatest Hits. That turned out to be the longest running single-presenter single-format popular music programme in British radio history. I am also the only broadcaster to have had regular series on BBC Radios 1, 2, 3 and 4. I have also co-written the bestseller, The Guinness Book of British Hit Singles. Everything since achieving those goals has been jam. I’ve been so blessed.

Q: What do you hope audiences will take away from “An Evening With The Great Gambo – The Professor of Pop”?

A: I hope people will recognise that there is a lot of possibility in life if you just follow your nose. Don’t be afraid to try what interests you. Following Elton John into the men’s room at the Royal Albert Hall is an extreme example, but it paid off. If I hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t have got into radio broadcasting in this country. I simply took the initiative. There is nothing embarrassing or shameful about taking the initiative. It doesn’t matter how many “no’s you get. It only takes one “yes”.

*An Evening with the Great Gambo, the Professor of Pop, Paul Gambaccini, is at Lighthouse, Poole, Friday, April 20. Call the box office for tickets.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here