Last week we turned our focus to the lives of impoverished labourers in Dorset in 1846.

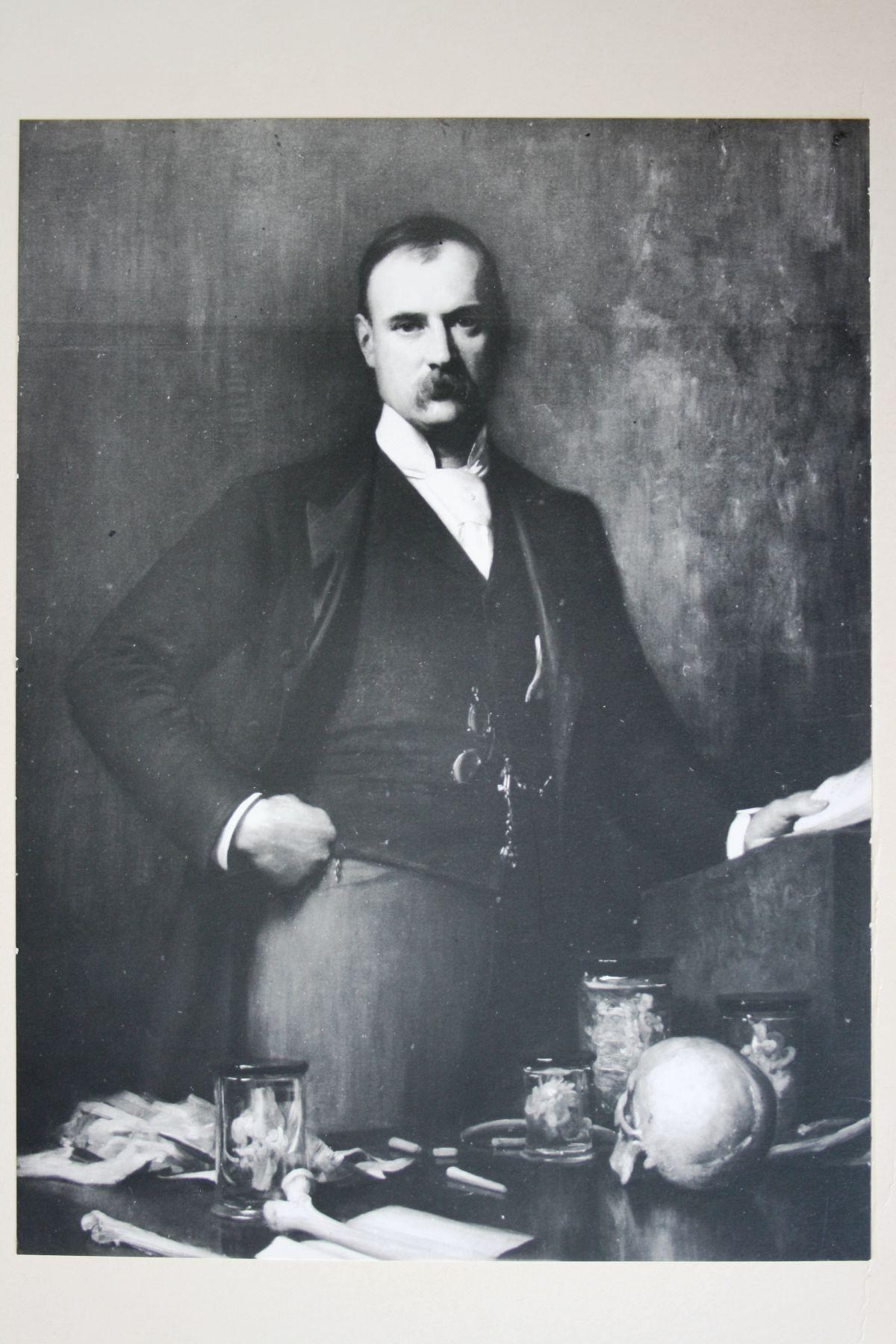

Roger Lane of West Stafford supplied us with a 1916 article written by Dorchester man Sir Frederick Treves and published in 1917 examining poverty in the county 70 years previously in 1846.

Sir Frederick, getting his information from the article published in the 1917 Annual Year Book of the Society of Dorset Men, was shocked to discover what life in Dorset was like for 'peasants' and wrote that significant progress had been made for labourers in the 70 years since.

He also wrote about how things in general fared in Dorset in 1846.

Sir Frederick, who gained fame as the man who looked after the Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick, notes that Dorchester still had a reputation as a picturesque town and the Old Town Hall was still standing against St Peter's Church in the county town - two years later the town hall was pulled down in 1848.

The hall is described as 'a very simple building of two storeys'.

In front of the windows was a balcony from which the Mayor made public announcements on occasions of solemnity, while below was an archway which led to the butter and poultry market.

Sir Frederick writes that Dorchester was 52 miles from the nearest railway station but the coach trade was booming.

"Seven coaches rattled into Dorchester, with horns blowing and harness jingling, every day of the week, and seven left with the same bustle and ceremony," he wrote.

Three days of the week saw nine coaches from Dorchester coming in and out - the main coaches were the Royal Mail from London via Southampton, the Magnet from London by the Salisbury Road, the Emerald from London by way of Poole and the Forrester that came from Exeter.

Sir Frederick writes that it was reported that people of Dorset regretted the coming of the railway at the expense of the disappearance of the coach. Dorset dialect poet William Barnes even wrote a poem bemoaning the change.

The year 1846 also saw Maumbury Rings in Dorchester threatened with utter destruction, Sir Frederick writes, because Brunel was determined to run the railway to Weymouth through the ancient amphitheatre.

In 1846, the Penny Post had been in existence for six years and the adhesive stamp was still a mysterious novelty.

Sir Frederick writes: "The first stamps were black and the obliterating mark was red. The ingenious soon discovered that the red marks could be easily washed off by simple chemicals, so it came to pass that half the lady's maids in the land and all the schoolboys were busy converting old stamps into new.

"In 1846 the postman, who wore a tall hat and was by reason of the noise he made a public nuisance, was forbidden to ring his bell when delivering letters."

At the time there were no telegrams and photography was still in its infancy, Sir Frederick writes.

Also in 1846 Louise Philippe was still on the French throne, the Corn Laws weren't repealed until June 26, 1846 and the Fleet Prison in London was not yet demolished. A copy of the Times would cost fivepence; income tax was sevenpence in the pound (it rose to 1/4 in the Crimean War) and prices for typical goods were 8d to 8.5d per 4lb loaf for bread; wheat 52/2, barley 7/4 and oats 23/6.

The Society for the Abolition of Duelling was founded in 1844.

Sir Frederick wrote that dress in 1846 was very familiar from old portraits.

"It was the age of tight lacing and ladies' dress was characterised by a wide skirt 'laden with many flounces', over which was worn a tunic of a different colour. The mark of respectability was the possession of a silk dress, just as a little later, no family could be genteel unless they owned a piano.

"The ladies adopted ringlets, or had their hair plastered to their heads by means of a bandoline. A close-fitting bonnet made of light straw and called 'a railway bonnet' was very fashionable."

Small boys were clad in nankeen trousers and green coasts in 1846, Sir Frederick wrote.

"On all occasions of ceremony they were expected to adopt white stockings and pumps.

"Men wore whiskers, high, open, pointed collars and voluminous stocks. Tall hats, also known as stove pipe hats, were the fashion to wear, even while playing cricket. Coats were pinched in at the waist but had ample skirts."

There was no difficulty in finding servants, Sir Frederick writes, with only a few adverts notifying vacant situations and columns upon columns of adverts from servants eagerly seeking places.

Many Germans were coming over to work in England, Sir Frederick wrote and there were constant notices, in German, of boarding houses were Germans could be received.

An advert caught Sir Fredericks's eye while he as looking through newspapers of 1846.

It read: "A German physician of experience wishes to travel with an insane English gentleman." What an agreeable couple, Sir Frederick remarked!

I

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel