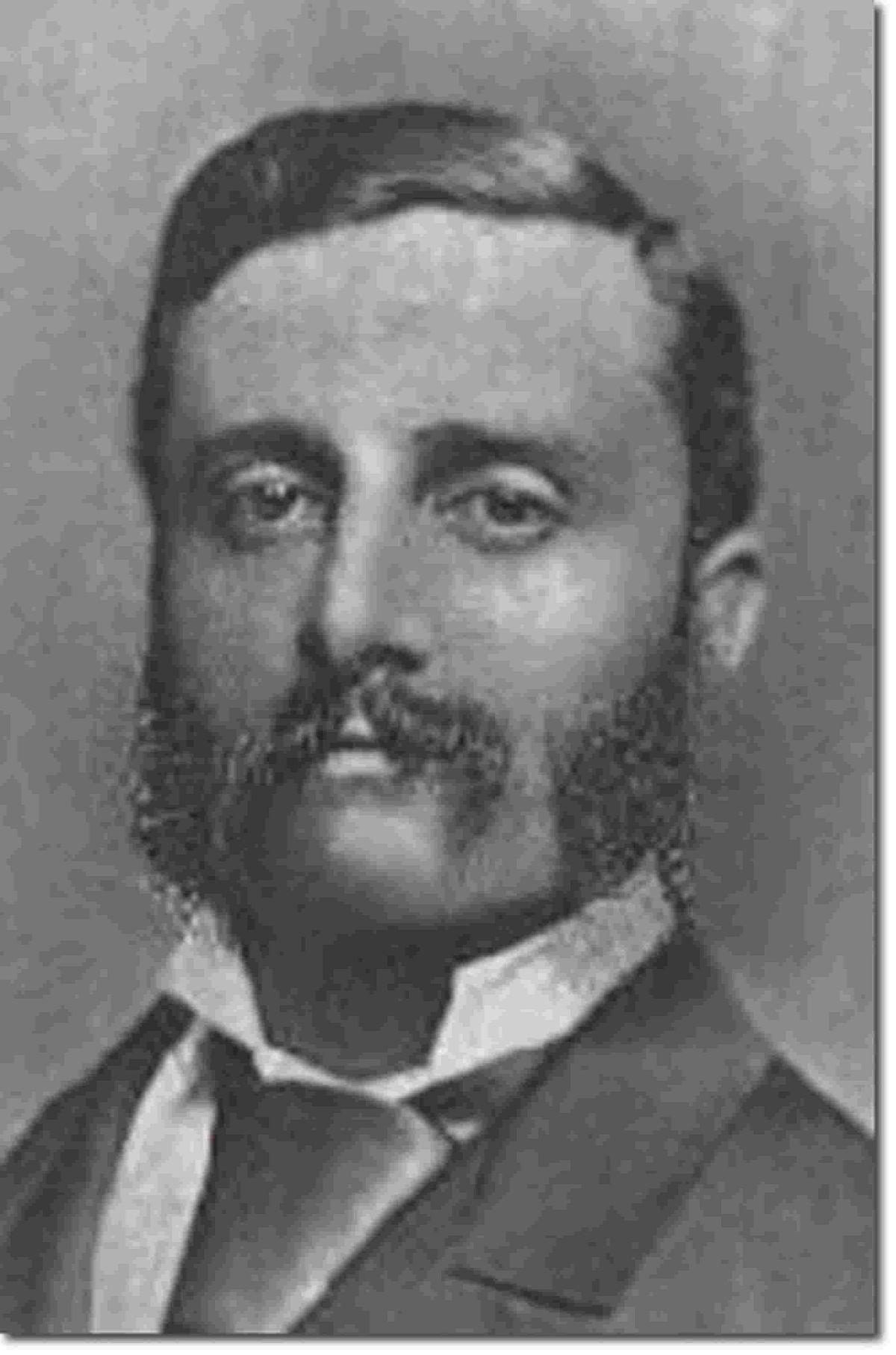

TODAY we are turning our attentions to the tale of Weymouth’s forgotten soldier, Reginald Younghusband.

There is a memorial to him at Melcombe Regis Cemetery in Weymouth alongside the head-stone of his father Thomas.

Thanks to Fiona Taylor, of Weymouth, who investigated his life, discovering that Reginald was part of the 5,000-strong British Army invading Zululand at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift in 1879.

He was born in Bath in 1844 and his father, Captain Thomas Younghusband, had worked for the Honourable East India Company.

Whilst in India, Thomas met and married Pascoa Georgina Barreto. Their first three children were born in India. On their return to Britain they lived at various locations before settling in Weymouth at the fashionable address of the then recently built No 12 Victoria Terrace (today 144 The Esplanade – Hotel Mon Ami) where they resided with their three servants.

After finishing his education at Corsham in Wiltshire, Reginald joined the Army and commissioned an Ensign on August 20, 1862, promoted to Lieutenant on August 29, 1866, and Captain on March 14, 1876.

A few months later he left Southampton for the Cape, in charge of 80 soldiers for the 24th Regiment.

On January 4 he came home, disembarking in Southampton and one month later he married Eve-lyn Davies at Marylebone London.

After spen-ding several months in England he returned to the Cape on August 2, 1878, aboard the Tyne.

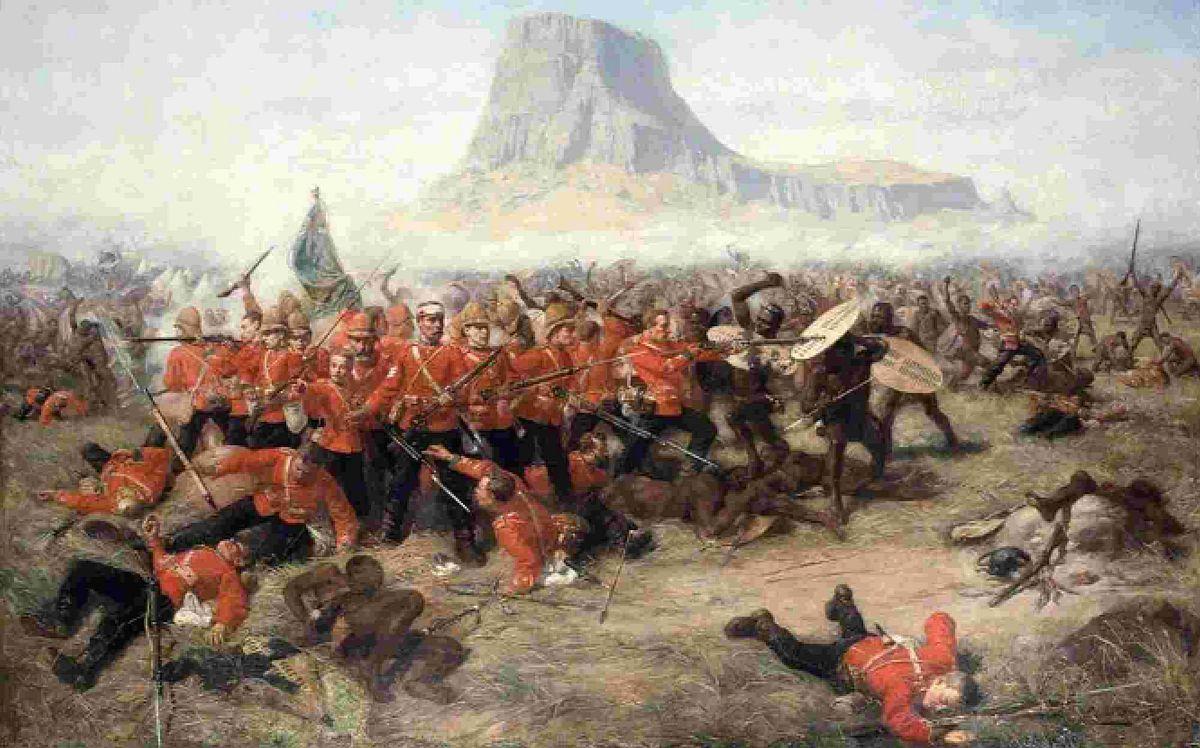

On January 11, 1879, Younghusband and the 5,000-strong main British column invaded Zululand at Rorke’s Drift and of course the film Zulu starring Michael Caine was made about the invasion. It was commanded by the ambitious Lord Chelmsford, a favourite of Queen Victoria, who had little respect for the fighting qualities of the Zulu.

“If I am called upon to conduct operations against them,” he wrote in July 1878, “I shall strive to be in a position to show them how hopelessly inferior they are to us in fighting power, although numerically stronger.”

The misjudgement of the British forces came to rebound on them badly.

Heavy rains had broken a drought and hundreds of ox wagons required to transport the army’s supplies had been mired in mud.

The main inv-asion column, commanded by Chelm-sford himself, had set up their camp on January 20.

It was on a wide plain under a hill that reminded many of the British soldiers of the sphinx on their regimental badge. The Zulus called it Isandlwana.

But at 4am on January 22, Chelmsford made the first of a series of blunders by taking two-thirds of his force off to pursue, towards the south-east, what he believed was the main Zulu army.

In fact 20,000 Zulus, led by their Commander Ntschingwao, were in the North East, lying in wait just five miles from the exposed and under-manned camp at Isandlwana. The Zulus rose as one and began their attack, using their traditional tactic of encirclement known as the ‘horns of the buffalo’. The horns would encircle the camp while the head and chest would crush it from the front.

But the left horn broke through the British firing line, while the right swept around behind Isandlwana and overran the camp and occupied the supply depot and ox-wagon train.

They separated the British from their ammunition supply and stampeded their oxen, sending about 4,500 animals careering across the veldt.

At the final stages of battle, Captain Younghusband commanded C Company of the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment of Foot (2nd Warwickshire).

Younghusband’s men caused heavy casualties amongst the Nokenke (Zulu) regiment as they came charging down the hill.

They retired to the lower slopes and held off the Zulus until ammunition ran out.

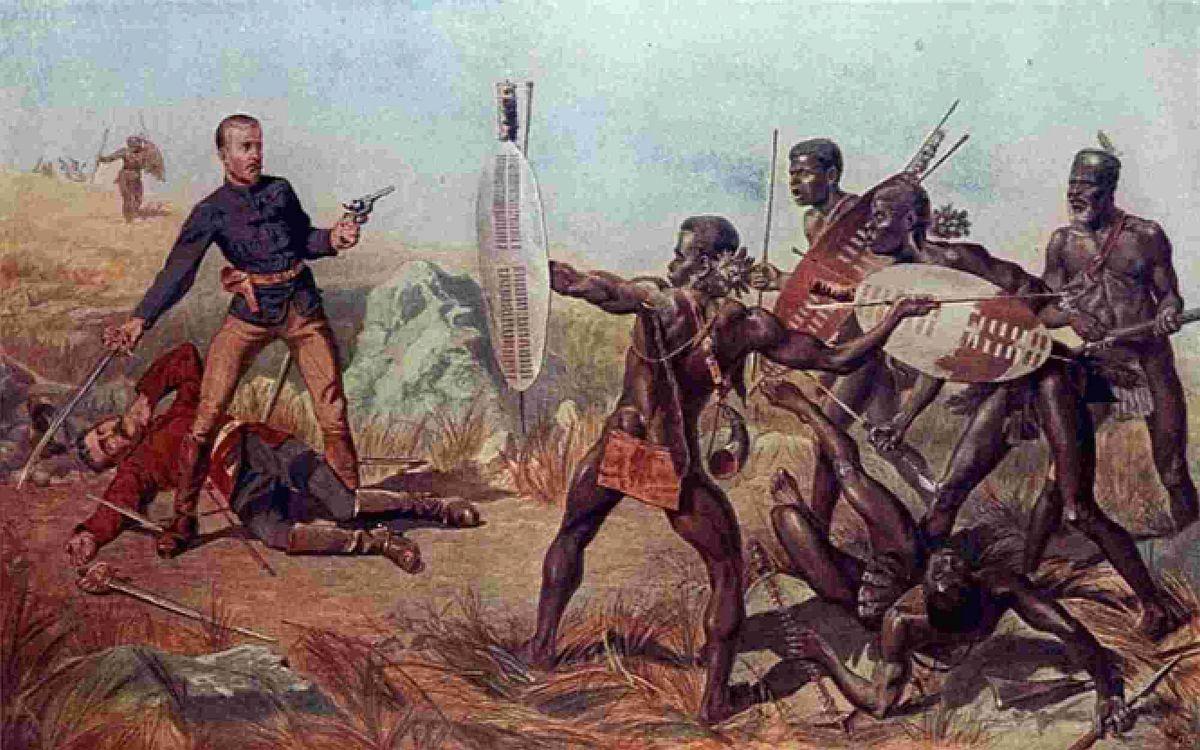

In his book The Washing of the Spears, Donald Morris recounts: “Captain Younghusband was one of the last to die.

“When C Company’s ammunition was gone, he had shaken hands with all his men and stayed to the end of the fight on the rocky platform over the wagon park. He had finally been forced over the edge with three survivors, and the four of them found some cartridges, clambered into an empty wagon and turned it into a rifle pit.

“They were rushed, and the three men were killed in the wagon bed, but Younghusband, minus his tunic, got away again and climbed into still another wagon. He was all alone, and the Zulus in his vicinity had stopped fighting, and when he opened fire, they scurried back hastily.

“He kept firing until all his cartridges were gone, and a few Zulus then tried to close with him.

“He bayoneted every warrior that laid a hand on the wagon, and he lasted for a long time until a Zulu finally shot him.”

The Zulus then carried Younghusband aloft on their war-shields back to the crag on which his men lay dead as they respected his bravery.

By 3pm, despite their own severe losses, the Zulus had captured the camp. The culmination of Chelmsford’s incompetence was a blood-soaked field littered with corpses – 1,359 British soldiers and hundreds of Zulus had been killed.

Word of the disaster reached Britain on February 11, 1879.

The Victorian public was shocked by the news that ‘spear-wielding savages’ had defeated the well-equipped British Army.

The hunt was on for a scapegoat, and Chelmsford was the obvious candidate. But he had powerful supporters in the Queen and the Prime Minister Disraeli.

The Queen showered honours on Chelmsford, promoting him to full general, awarding him the Gold Stick at Court and appointing him Lieutenant of the Tower of London. He died in 1905, at the age of 78, playing billiards at his club.

Today the sweeping plain leading up to the rocky mountain known as Isandlwana is dotted with 269 white washed stone cairns. Underneath lie the bodies of 1,329 British soldiers.

And in Weymouth stands a small, understated, loving memorial to a son that never came home.

The headstone of Thomas Younghusband with its memorial to his son Reginald. Thomas died just a few months after his son’s death.

- History buff Fiona runs a website suggesting interesting historical walks people can complete in and around Weym-outh. Among the walks she has devised are Georgian walks and a World War One walk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here