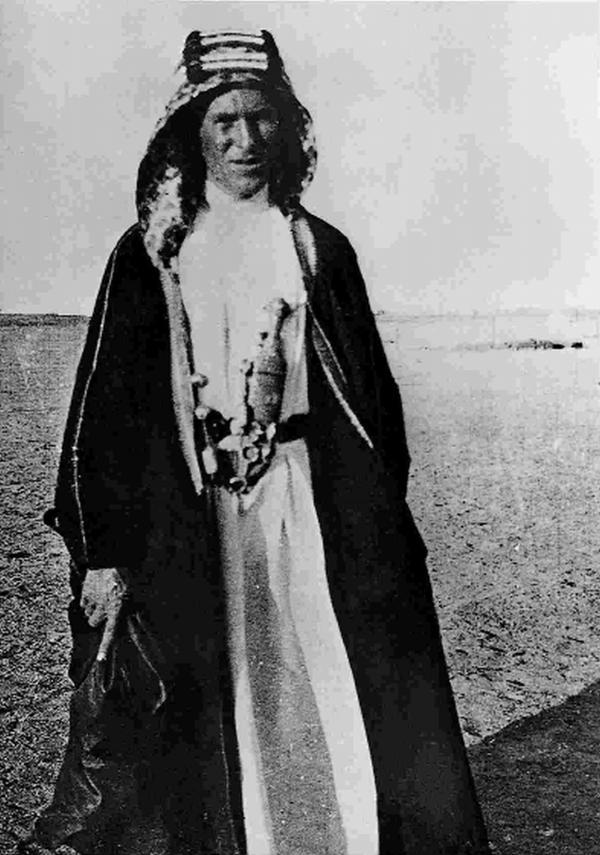

Lawrence of Arabia, who spent his final years in Dorset and lies in Moreton graveyard, was one of the most enigmatic and controversial heroes of the First World War.

His self-perpetuated legend grows ever more intriguing. Every piece of memorabilia pertaining to Lawrence is snapped up by enthusiasts and mystery and conspiracy were never far away in life and in death the body lay in a plain elm coffin. There were no flowers, no inscription.

No guard of honour lined the route to the graveyard, just a few villagers and ordinary soldiers there to see it past.

The great figures of the British Empire attended, but in line with the deceased’s request, no sign of position or rank was shown.

Alongside walked shopkeepers, mechanics, policemen and ordinary members of the public. It was the funeral of T E Lawrence, one of the most famous, revered, tragic and bizarre heroes of the British Empire.

Fifteen years earlier, in 1920, he had the world at his feet.

The so-called uncrowned king of Arabia had spearheaded one of the First World War’s most daring and subversive military attacks, bringing to an end 500 years of Ottoman domination of the Arabs.

Feted by the press, with the rich and famous clamouring to meet him, with titles, an influential job and illustrious future beckoning, he turned it all down to become a lowly recruit in the army.

Ned to his family, he was born in Wales on August 16, 1888, the illegitimate son of an aristocrat who ran away with his mother when she was nanny in his household.

As a child, Lawrence was a cauldron of emotions.

His father treated him as a friend, while his mother gave him and his brothers regular thrashings.

She protected her sons’ development almost maniacally. A friend said she never wanted her sons to marry and indeed when two of them did, one broke the news to her through a go-between, the other by letter.

For Lawrence, the beatings became character-defining. Later in life he would pay a man to whip him for sexual gratification. In adolescence he’d put himself through days without food and sleep, and harsh physical tests such as gruelling walks and bicycle rides. Colleagues regarded him as a true eccentric.

He did much to encourage an image of aloofness, but in fact his desire to be the centre of attention was just as great.

He also romanticised the idea of living in society’s lowest strata. On his first archaeological expedition to Syria in 1911, he remained diffident with English colleagues, but immediately immersed himself in the culture and language of the Arab workers. His love for their way of life and his hatred of the Turks grew quickly. And the Arabs themselves warmed to Lawrence, who became a patriarchal figure, once settling a 40-year squabble between tribes with a discussion in his living room.

When war broke out in 1914, Lawrence was posted to the Arab Bureau in Cairo, working as an intelligence agent promoting the Arab rebellion. Sent on a mission to Prince Feisel in the desert, he became involved more directly, carrying out numerous attacks on the Hejas railway, the Turks’ only line of communication to Medina.

Although regarded as something of a sideshow in the Allied campaign, Lawrence’s work on the eastern flank of the British Army made masterful use of limited resources and ill-disciplined troops – and caught the imagination of a British public.

His greatest feat during the war was the taking of the Turkish port Aqaba, depicted in David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia, which Lawrence managed after a 600-mile detour through the desert and a series of guerrilla raids on Ottoman camps.

In the final charge, Lawrence was forced to overcome one of his worst fears – hand-to-hand combat with the enemy. But as he thundered down on his camel with the Arabs towards the Ottoman position, Lawrence suddenly fell to the ground with a thump and blacked out. He’d accidentally shot his own camel in the head and missed the entire battle.

Lawrence’s Arabic was good enough for him to make undercover recess into enemy territory, but on one occasion suspicious Turk soldiers noticed his fair skin and he was arrested.

Taken to the house of a local dignitary, he was stripped naked and whipped and raped repeatedly.

Later commentators have cast doubt on the story and it’s clear today that, while he did suffer some such fate, part of it was exaggerated. The experience, though, soured Lawrence’s attitude towards his position in Arabia and although he fought for Arab interests, he never returned after the war.

After the war, Lawrence described his experience in his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, admired as an example of fine writing but now shown to contain several deviations from the truth.

Lawrence’s career in the military intelligence was based on him telling lies and he was a natural for the job. He had been creating a Lawrence legend all his life.

The mystery continued when he shunned the limelight and under the name John Hume Ross, in 1922, joined the RAF. Later that year he was found by the Daily Express and the publicity forced him to leave.

But still seeking subservience in life, as TE Shaw he joined the army at Bovington. There he discovered what would become his home and haven – the tiny, dark, boxlike Clouds Hill cottage.

Lawrence often spoke of the barbarism of his forces colleagues, but he didn’t bar them from sharing his retreat. Turning up unannounced, they would sit, somewhat out of place, listening to Beethoven or Mozart, eating baked beans out of the tin and drinking china tea. Alcohol never entered Clouds Hill.

His abstemiousness extended to the decor. Clouds Hill was left almost as bare and spartan as the day he found it. Lawrence even refused a sheet and blanket, using only his sleeping bag.

Terence Rattigan’s play Ross, based on Lawrence’s first period in the RAF, highlights the double-sided aspect of his life. One scene depicts Lawrence, or Ross, hauled up before his superior for returning late to camp after a dinner party in London.

When the irate officer asks Lawrence to reveal who was at this dinner party, the lowly aircraftsman reels off a list of some of the most influential people in the country, including the prime minister.

Among Lawrence’s circle of distinguished friends were Thomas and Florence Hardy who lived at Max Gate, near Dorchester.

Hardy and Lawrence was a meeting of minds. Although in his early 80s and approaching death, the country’s most famous writer was still a match for Lawrence’s philosophical musings, while Florence called Lawrence “the most marvellous human being I have ever met”.

It’s widely accepted that Lawrence was homosexual. He once admitted he was “frigid” with women, but he did enjoy close female relationships, as long as they remained platonic.

He did awkwardly propose to childhood friend Janet Laurie in 1905, but when she spurned his advances, he asked a friend to take her out, while he watched from a distance.

The autobiography of Viscount Maughan records the story of a lance corporal at Bovington in the early 1920s, who was invited by Lawrence to Clouds Hill one afternoon. There, he was persuaded to whip Lawrence and have sex with him.

In June last year it was revealed that Lawrence wrote bizarre letters under a pseudonym to a Southampton swimming baths instructor in the 1930s. Posing as a concerned uncle, he asked for disciplinary training to be given to his nephew. The nephew was in fact Lawrence himself.

The army gave him the austere discipline he craved.

Captain Kirby, Shaw’s superior officer in the Tank Corps, recalled: “He received no favours and asked none. He was very amenable to discipline, much more so than the ordinary soldier, and the fact that he had once been a Colonel was never displayed in his behaviour. In fact, he was a perfect Tommy Atkins.”

The motorbike was Lawrence’s great release. Roaring at high speed through Dorset’s towns, frustration over publishing deals for his autobiography and everyday woes were quickly left behind.

And he wasn’t averse to investing large amount of money in his hobby. His first Brough was bought in 1923 for £150, more than the cost of an average house.

Lawrence won the respect of his colleagues when he took them for rides on his bike around the camp and often he’d boast, boy racer-like, about how quickly he’d managed to reach his destination. But the bike was also to bring about his death.

Speeding along the road between Bovington and Clouds Hill, he failed to spot two boys on bicycles, clipping one of their back wheels, swerving away and somersaulting over the handlebars onto his head.

As the world’s press descended on Dorset, headlines screamed and rumours of assassination abounded as one of the world’s most enduring legends slipped into a coma and died.

The world, as a tearful Winston Churchill said at Lawrence’s funeral in Moreton, would never see his like again.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here