The debut book by Tolpuddle photographer Paul Williams, Wildlife Photography: Saving My Life One Frame at a Time, is a book like no other. Laura Hanton speaks to Paul about the book's inspiration

BREATHTAKING images of herons and hares appear in Paul Williams's new book alongside his candid accounts of life with Post Traumatic stress Disorder (PTSD).

Paul's illness was sparked by a traumatic incident experienced while serving with Dorset Police. Juxtaposed with open and honest extracts about his struggles with mental health in Wildlife Photography: Saving My Life One Frame at a Time are tips and tricks about wildlife photography, from suggestions on equipment to advice on camera techniques. The end product, then, is a part autobiographical, part self-help book that highlights the value of nature for both physical and mental wellbeing.

A former solider, Paul, 59, had studied for a degree in mental health nursing and worked as a physical training officer at Blandford Camp before joining the police force and serving the area of Boscombe. Then everything changed.

"One day in 2010, a woman came in wearing a long black coat," Paul recalls. "She suddenly pulled out a massive samurai sword and started to threaten people. I managed to evacuate everybody, but then she came towards me. I had to use pepper spray to disable her."

Paul received a commendation for his bravery, but saw his actions as just "something we do."

"I took it on the chin," he says. "It's the kind of thing thousands of police officers deal with all the time, and some of them aren't as lucky as I was."

Yet a few months later, it became clear that the incident had not been as insignificant as Paul believed.

"I drove to the hospital one day convinced I was having a heart attack," he remembers. "Turns out, there was nothing wrong with my heart at all, and I was actually having a massive panic attack. "That was the beginning of my breakdown."

For a long time, Paul was in denial that anything was wrong. When he finally accepted what he was suffering from, he made three severe attempts to take his own life.

"I just felt that if this was going to be the rest of my life, then I didn't want to live it."

Fortunately, Paul received support from the Community Mental Health Team (CMHT), who offered him a therapy called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). The practice helps people heal from emotional distress through the use of sensory input, such as eye movements or hand tapping.

"It gave me a break," Paul explains, "and it gave me some time to reflect. It was during this time that I spotted some mice and voles in my garden. I started to take photos of them and chart their progress."

With little experience and having previously only dabbled in photography, things developed from there. Paul began posting images online, and won a couple of photography competitions. He then began working with Dorset Wildlife Trust, which he continues to do today, running workshops and photography courses on Brownsea Island. Paul says the whole process gradually gave him a sense of purpose.

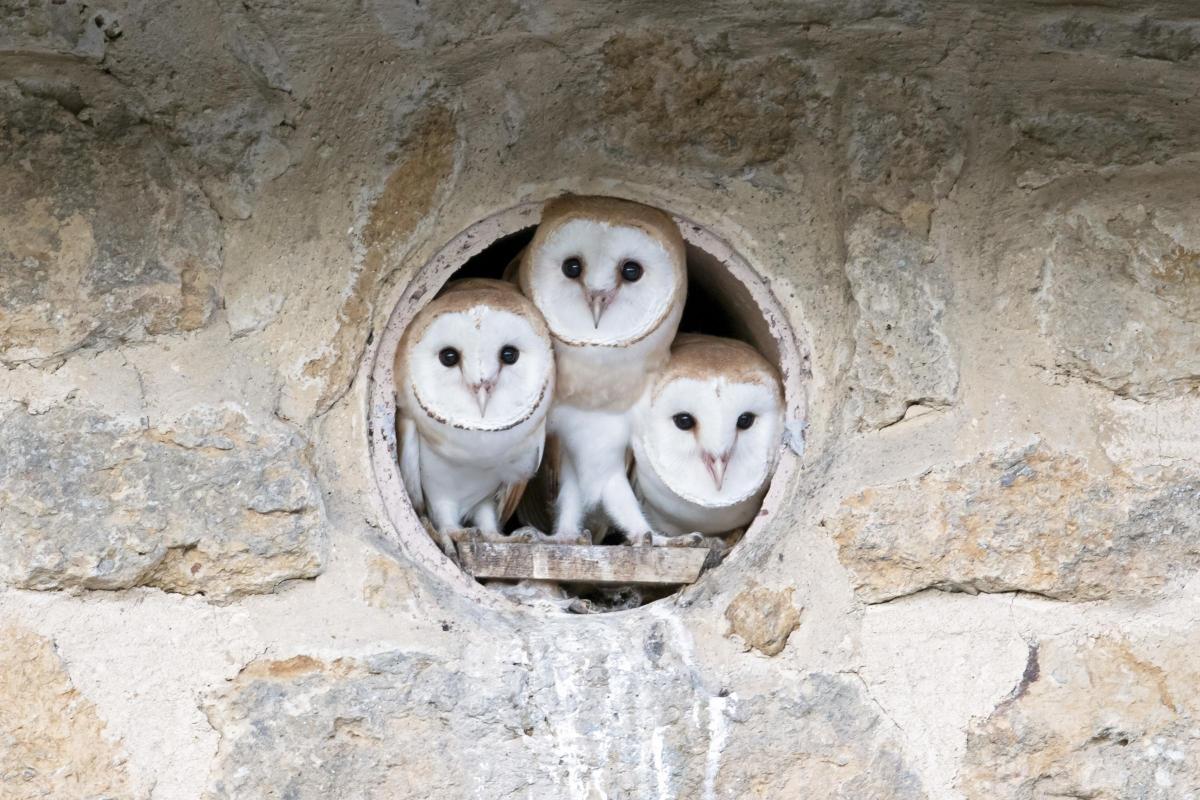

"It filled the vacuum that was left from leaving my career when I was at the top of my game," he says. "Taking photos gives me a sense of peace and satisfaction. I get a thrill from sitting still and capturing something that not many other people get the opportunity to see."

It took Paul just under a year to create his book, which features wildlife images from all over the world. In recent years, Paul has travelled to Scotland, Sweden and Alaska to photograph some of the finest aspects of nature, but travelling is not something he finds easy, and his recovery is ongoing.

"Heathrow is pretty much the worst place in the world for someone with PTSD," Paul says, "but I know on the other side of the flight, there'll be something amazing worth photographing. "Generally, I try to avoid crowds, and I still have nightmares and flashbacks. I'm definitely not out of the woods, but I'm no longer in the forest."

While the process of writing and promoting the book has been challenging, bringing up certain memories and forcing Paul to reflect on difficult experiences, it has also been undeniably cathartic.

"I draw strength from telling my story," he says. "I've realised that alpha males have still got their heads in the sand when it comes to mental health and suicide. I want people to know that it's OK to ask for help, and that however they feel now, there will be a better day."

So far, the response to Paul's book has been overwhelmingly positive, receiving praise from both photography enthusiasts and people suffering with mental health difficulties. It has even been endorsed by naturalist and nature photographer, Chris Packham.

"He's been very open about his diagnosis of Asperger's and the challenges that brings, so we sent him a copy, and he loved it," Paul explains. "It's amazing to have the support of someone of such high calibre."

He adds: "The ultimate thing I've learnt is that sitting at home isn't going to make things better. Nature can be a tonic for both physical and mental health."

*Wildlife photography: Saving My Life One Frame at a Time is published by Hubble & Hattie, and is available now from Amazon and all good bookshops.

For more information about PTSD and other mental health conditions, visit www.mind.org.uk and for 24/7 support, contact the Samaritans on 116 123, or visit www.samaritans.org

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here