ORDINARILY they would never be mentioned in the same breath but a judge coupled an incompetent burglar and a future Prime Minister over their daring escape attempts by train.

Recorder Peter Schiller KC made the unique observation after hearing how George Manuel, 29, had ridden on the buffers of a London-bound goods service.

“He had some pluck,” the judge remarked. “He seemed to be trying to copy Winston Churchill in the Boer War.”

Manuel, a ship’s fireman, was unsuccessful, unlike Churchill who as a news correspondent had been travelling on an armed train, loaded with British soldiers, which crashed into a boulder placed on the line by a Boer commando force.

In his desperate attempt to flee, Churchill found himself, some 80 minutes later, trapped in a gully near the track – defenceless and exhausted, he surrendered to a lone horseman who pointed his rifle at him.

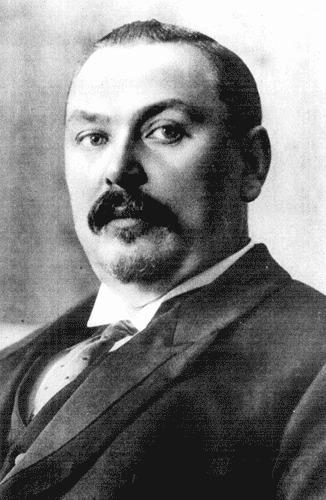

It was a freak moment in time. His personal captor was General Louis Botha and both men were to become prime minsters of their respective countries.

The Boers realised they had acquired a massive bargaining tool with Churchill, the son of the distinguished politician Lord Randolph Churchill with an ancestry stretching to the first Duke of Marlborough who had won the Battle of Blenheim.

Detained as a prisoner of war in a converted school in Pretoria, he soon discovered there were voids under the flimsy floorboards and escaped, vaulting over a wall to scour the streets in search of the railway that headed east. Principally hiding by day and hitching a series of rides at night on a series of slow moving goods trains he eventually made it to Mozambique and safety.

But there was to be no successful outcome for Manuel who, armed with a knife and keys, broke into a pawnbrokers shop in East Street, Southampton, through an open first-floor window in the early hours of July 28, 1931, with accomplice Fred Woods, a 27-year-old labourer.

Unsurprisingly, as they had been drinking, their entry was far from silent and quickly disturbed the manager who held them at gunpoint until the police arrived.

The same morning, charged with housebreaking, they appeared before the town magistrates who remanded them overnight to Winchester Prison pending their trial at the quarter sessions the following day.

Manuel, a ship’s fireman, was seen exercising in the prison grounds between 7.30am and 8am but minutes later he was found to be missing. No one saw him go and a thorough search of the jail failed to find him.

Police issued an urgent public appeal to be the lookout for the fugitive who was 5ft 9in, of fresh complexion, with brown hair, blues eyes and of stout build.

Adopting a fake American accent, Manuel encountered George Parsons on his way to work who gave him directions for the goods yard – a fatal mistake.

Hours later while at home, the gardener began reading the Echo and realised who the stranger was. He contacted the police who concentrated their hunt on the railway.

Manuel, meanwhile, had hidden in a cornfield still to be harvested and waited for the first appropriate goods train to board. He eventually clambered on one, sitting astride a buffer.

He still may have made good his escape but by chance a signalman at Micheldever saw his outline. He rang colleagues who in turn informed the police and the train was stopped in the middle of the Hampshire countryside.

Manuel bolted across fields but a much fitter Pc Saunders gave chase and after a brief altercation was caught. He was then led back to the hamlet and, accompanied by the constable, was taken back to prison by taxi.

On the way, Manuel confessed he had no intention of appearing in court if he could help it, disclosing he had escaped from prison by climbing on to a roof and disappearing over a wall at the back.

The circumstances of his recapture were revealed to the judge when the ship’s fireman appeared before him later the same day along with Woods.

Detective Inspector Percy Chatfield said he knew nothing of either men and could not verify his claims that he came from Liverpool and had lost his father in the First World War.

Woods told the court he had met Manuel a month earlier and they had decided to come to Southampton to find a ship so he could return to his native New Zealand.

“This offence occurred when we were a trifle drunk and as a matter of fact we both had some whiskey on us.”

The judge interjected: “So you are not without money.”

Woods replied: “I ran into a fellow I knew and he gave me the whiskey that afternoon.”

When asked what he had to say, Manuel succinctly responded: “Only that I am guilty.”

Jailing him for three months, the judge said he could not think what induced Manuel to turn to crime.

“As far as it is known, there is nothing recorded against you but I cannot overlook the offence. You went out with an electric torch, a knife, keys and you broke out of prison. Be thankful you are not indicted for that. As this is your first offence, I will give you a light sentence.”

Woods, however, escaped a term behind bars, being bound over for a period of 12 months so the probation officer could find him a ship to return him home.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here