Dorset Echo Centenary: Llewelyn Powys, the Echo’s Greatest Writer

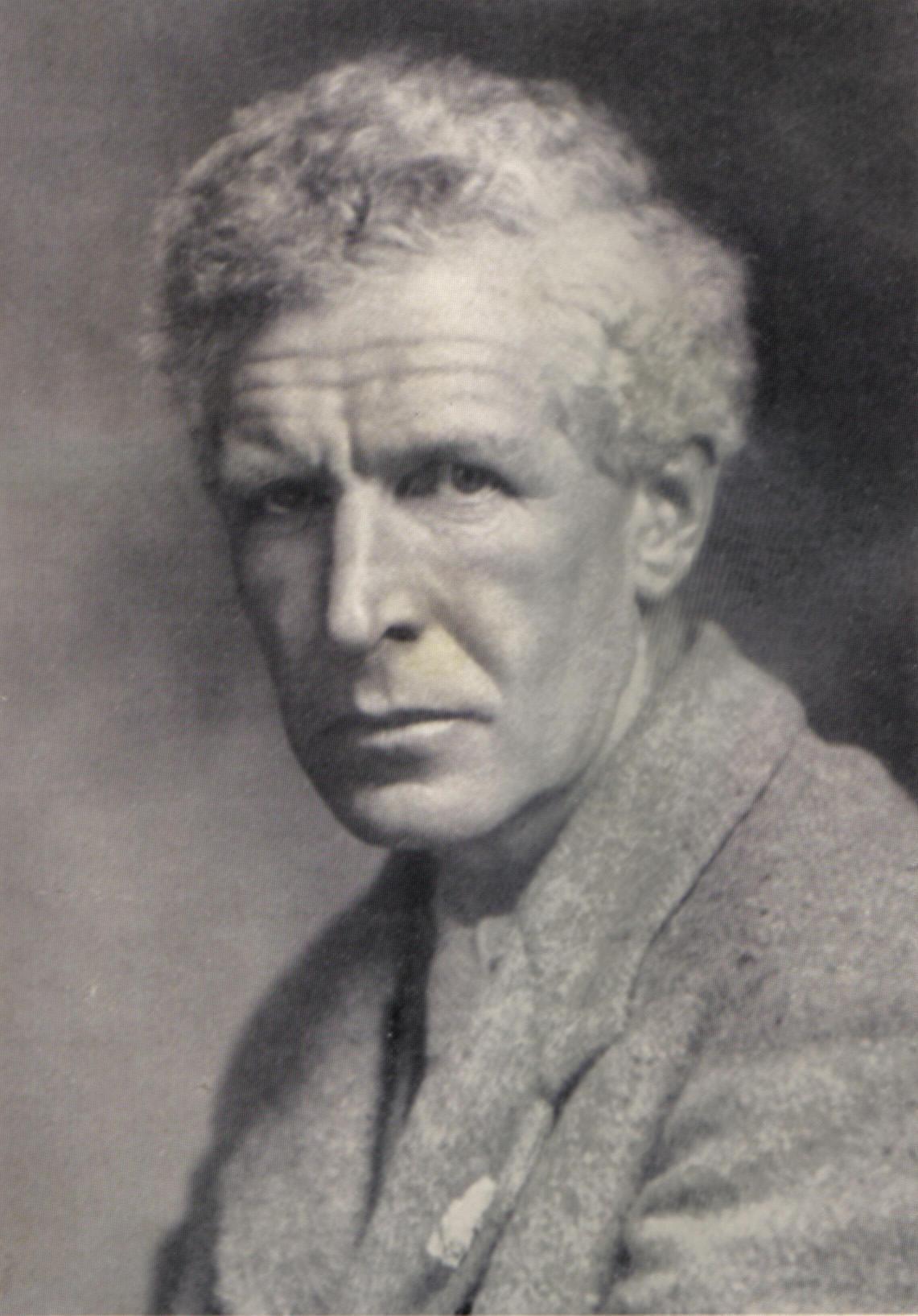

Born in his “dear natal town” of Dorchester on August 13, 1884, Llewelyn Powys’ literary reputation has stood the test of time as a major Dorset writer alongside Barnes and Hardy. In recent years a number of his books have been republished in new paperback editions by The Sundial Press, Little Toller Books and the Powys Press.

I share his love of both Somerset and Dorset, and of Kenya and the USA, two foreign countries where he went to live and work, countries which have also played an important part in my own life, however different our experiences. He worked as a stockman in Kenya, about forty miles from my beloved Lake Naivasha. These coincidental parallels do not explain my deep admiration for his profound and beautiful prose. His Dorset Essays (1935) and Somerset Essays (1937) were the first of his books which I came to treasure, before moving on to his two earlier books about Kenya (Ebony and Ivory, 1923 and Black Laughter, 1924). Since then I have collected many of his works, philosophical as well as landscape-inspired. I would love to have the space to quote more extensively from his books, letters and essays.

In Dorset he went to school in Sherborne, and lived for various periods in Weymouth and East Chaldon. His time in Weymouth started well. In October 1919 he wrote to his brother John that he found the surroundings in his father’s house at 3 Greenhill Terrace very much to his taste. He was writing every morning (he wanted to try writing for the papers). By early 1920 he was feeling like a failure, despondent and anguished by his existence in Weymouth, no longer able to tolerate his little room and the house at 3 Greenhill Terrace. In ‘Discontent’, the first chapter of “The Verdict of Bridlegoose (1926), he goes further. Depressed after his return from East Africa, the author feels nothing, finds himself inattentive and unmoved by the beauty of Dorset, the once-familiar sights of the Chesil beach, by "the winter stars shining at midnight upon the backs of Dorset sheep, asleep on Dorset downs":

'Never had I experienced a deeper discontent than I felt at my father's house at Weymouth after my return from Africa...Whenever I took up my pen a heavy melancholy weighed me down. "Had not I, in my time, heard lions roar?"...I, the lover of life, the son of the sun, became a renegade and remained unmoved before what I had always held most dear...Of course I realised perfectly well the cause of my predicament. Nothing else, in fact, than that it was my misfortune to belong to, to have been born into, the English middle class. For after all, what a terrible class it is; merely to have occasional intercourse with the people who belong to it is awful enough, but to be born one of them! It is like finding oneself in an enormous wire trap unable to get out. You can get in; anybody can get in, but you can't get out.

In July, I went to Southampton to meet my brother John, who was returning from the Unites States for a holiday. As we sat together on the wharf he asked me whether I would not consider going back with him to America. I answered without hesitation that I would go back with him. Had not I been feeling for the last twelve-month that it was high time for me to be setting out on my travels again, to be setting out on my travels for a new jungle? I had no mind to remain any longer under my father's protection, cooped up like a prize hen. I would rather starve, I thought, in a garret of New York City than live so mean a life".

So he decided to join his brother in America.

In New York he worked as a journalist from 1920-1925. He was glad to go, after his dispiriting year in Weymouth, but he would be relieved to come home again. His book, Skin for Skin (1926), which begins at the time he first discovered that he had tuberculosis, at the age of twenty five, concludes with him back in familiar Dorset countryside.

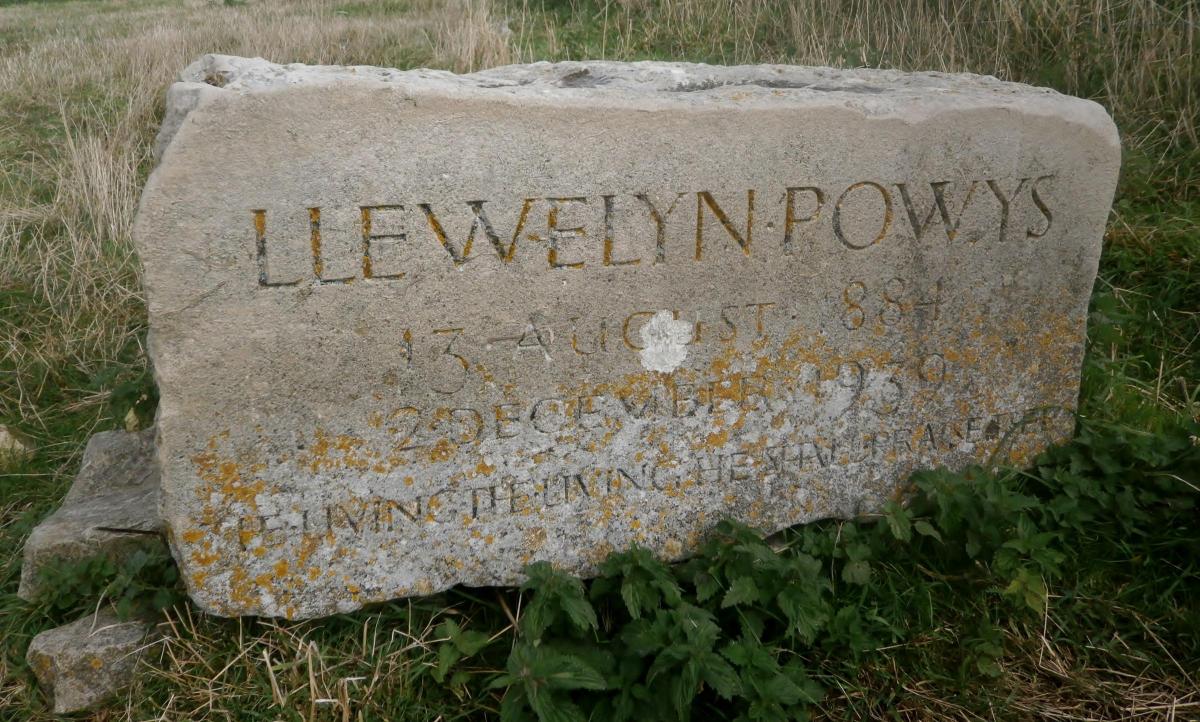

I have often walked along the same paths and cliffs he knew so well around East Chaldon and I always stop to admire the block of Portland stone carved by Elizabeth Muntz (Llewelyn’s ashes are buried beneath it). He had died in Switzerland on 2 December, 1939.

If in a mood to meditate, I recall what he said on his deathbed:

“Love life! Love every moment of life that you experience without pain”.

If walking alone, I might pause longer, to think of other words of wisdom which I have noted down:

"No human being should ever wake without looking at the sun with grateful recognition of the liberty of another day; nor give himself to sleep without casting his mind, like a merlin, into the gulfs between the furthest stars." From "Natural Happiness” (in Earth Memories).

“The unspeakable privilege of merely being above ground”. From “Death”, in Ebony and Ivory.

"Is it not absurd that we cannot be happy in our little life that is so soon over? Yet who can regulate the lone cry of the curlew or the cry of the eagle in the clouds!" From a letter to H. Rivers Pollock, 1930.

Whenever I take my grandchildren to visit the Bovington Tank Museum I am reminded of Llewelyn’s letter from Gilgil, Kenya, to his brother Theodore on June 11, 1918: “The anomaly of war at this stage of our civilization is clearly seen by the importance which becomes necessarily attached to work, to action- to constructing a tank and carrying a bayonet efficiently. Tanks should be constructed in the mind – such tanks would really avail the human race- religion, poetry, philosophy- these things only are of use”.

If religion ultimately came to mean less to Llewelyn Powys than his increasingly atheistic and epicurean philosophy, his books have availed the human race generally as well as those fortunate to live in the West Country. In the often-quoted words of Philip Larkin:

“Llewelyn Powys is one of those rare writers who teach endurance of life as well as its enjoyment”.

In this article I wanted to focus some attention on his journalism, and especially on his association with the Dorset Echo. Strangely, he does not merit a mention in the special commemorative publication to mark the centenary of the paper (first published on March 28, 1921). Even stranger are the words of Van Wyck Brooks about Llewelyn, soon after the Englishman’s arrival in the USA (from Brooks’ introduction to an online edition of Earth Memories):

“One could scarcely imagine him reading a newspaper – his style is untouched by newspaperese”.

Van Wyck Brooks had first met him in 1921, in the New York office of The Freeman.

Llewelyn Powys went on to write nearly forty articles for the Dorset Daily Echo between 1933 and 1939. It would be wonderful if the Dorset Echo could reproduce them in a special commemorative booklet for this centenary year. A list of his articles for periodicals can be found at powys-society.org/1PDF/LLP-CONTRIBS.pdf

Although an undoubted master of English prose, Llewelyn was first and foremost a great communicator whose newspaper and periodical articles appealed to readers from all walks of life, whether living in town or country. As Judith Stinton writes in Chaldon Herring, The Powys Circle in a Dorset Village (1988)

“Whilst at Chydyok, he worked on despite his illness. In 1933 he was writing Love and Death, but found himself more often composing ‘very short and utterly “perfect” articles for the Dorset Echo’ which he much enjoyed doing, as he explained to Rivers Pollock: ‘I have a mania for doing this. I like the idea of giving to the Dorset labourers and shepherds and furze cutters the very best writing and it thrills me when I hear of some essay being discussed in a Dorset tavern’.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel