WE'VE been looking at one of the biggest contributions Dorset has made to this country - Portland Stone.

Looking Back has been delving into the pages of the fascinating new book 'Stone to Build London' by Gill Hackman.

This week we're looking at how Portland Stone proved invaluable after the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the island met increased demand.

For rebuilding St Paul's Cathedral in 1676 Thomas Knight, a stone merchant from London, acted as an agent on Portland.

He proved to be unreliable and failed to despatch stone as required and failed to pay the quarrymen according to their contracts with him.

In 1678 he was replaced by Thomas Gilbert and Thomas Wise. Gilbert was a Portlander who, after his apprenticeship in London, had become a stone dealer.

Wise was the son of Thomas Wise, a London mason.

Various agents would come and go, such was the scale of the task.

Hackman writes: "Sir Christopher Wren was still worried about the supply of Portland stone.

"He claimed that stone was being wasted on the island by irregular and improper working.

"He claimed to Queen Anne that because of irregularities among the workmen there was likely to be a scarcity of stone and the price would be enhanced.

"This led the Queen, in September 1703, to forbid all persons from taking stone or working in the quarries without licence from Wren."

Arguments continued and the rules weren't enforced, but the re-building of St Paul's Cathedral was completed in 1708 and the rights of the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's to obtain stone on the island ceased.

Hackman writes: "It is difficult to get a clear idea of the overall scale of quarrying at this time, but what information there is suggests that average annual exports of stone may have been in the range of around 2,000 to 5,000 tons a year.

"An overall figure of around 50,000 tons of Portland stone is often quoted for the construction of the cathedral.

"Other buildings are unlikely to have used more than 1,000 tons a year in total."

The expansion of the stone industry led to new building on Portland, most notably the large new house at Fortuneswell of Thomas Gilbert III.

Between 1700 and 1800 there was a lot of building in London to accommodate its increasing population.

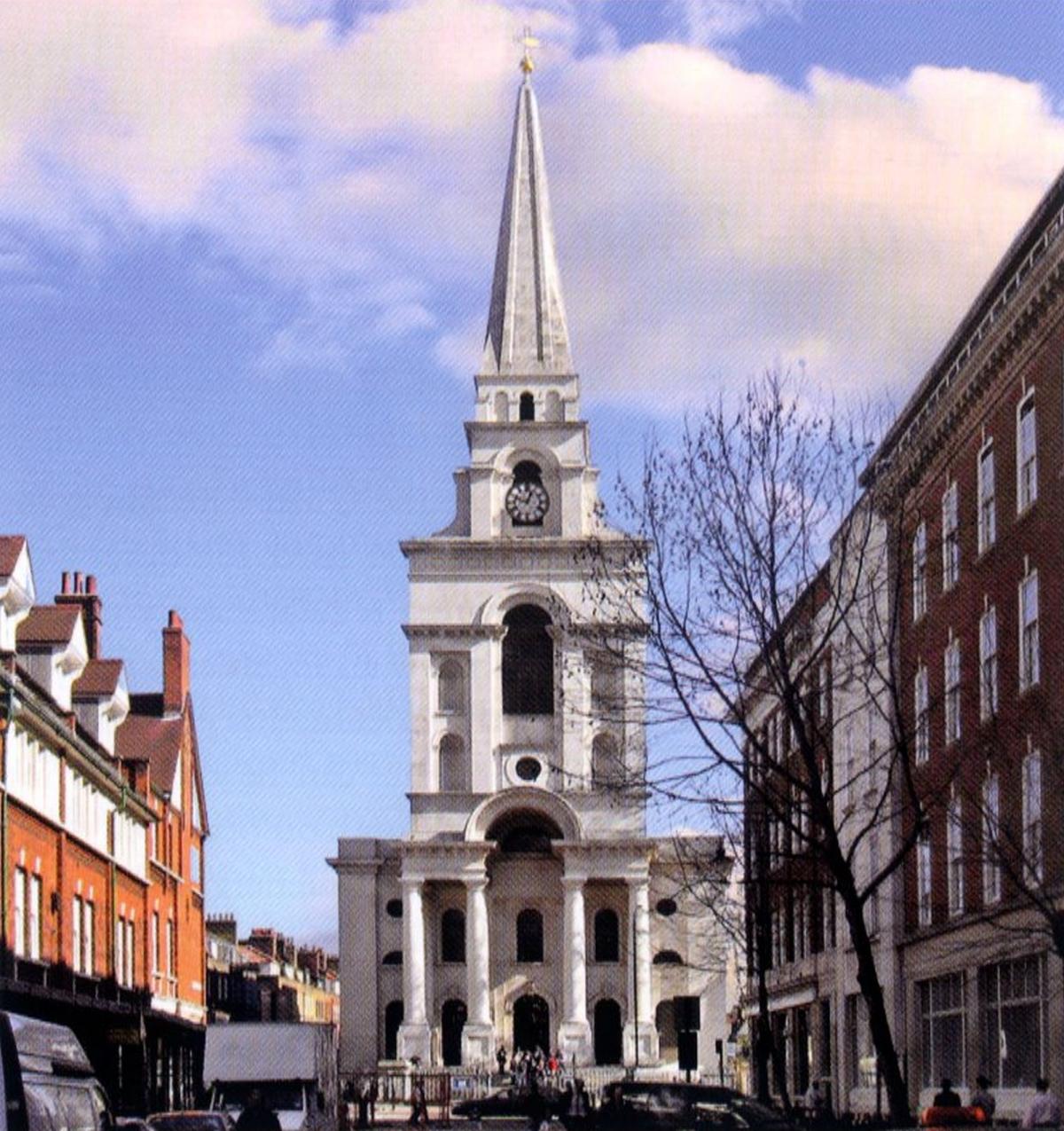

Christchurch Spitalfields church, with a tower and spire rising to 225 feet, was covered in Portland ashlar and built between 1721 and 1729.

St Martin in the Fields, which opens on to Trafalgar Square, was built between 1721 and 1726 using 'the best sort of Portland stone'.

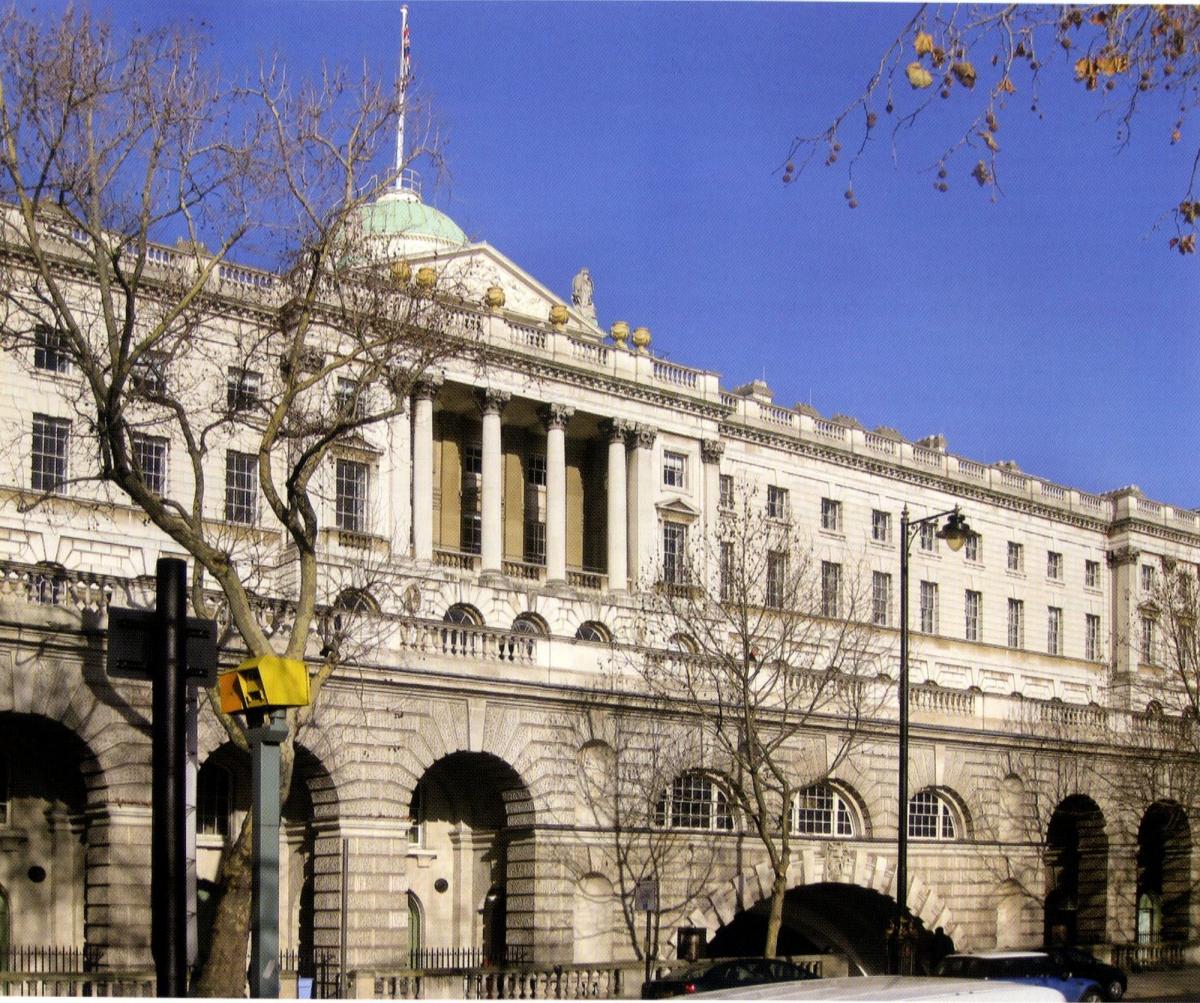

The stunning west front of Westminster Abbey was built using Portland stone, along with The Admiralty, the Horse Guards and Somerset House in The Strand.

Blackfriars Bridge, spanning the Thames, was built during the 1700s.

Artist Edward Rooker painted a picture of its construction.

Back on Portland, Pennsylvania Castle was built near Church Ope coast on the east coast in 1800.

John Penn, the grandson of the founder of Pennsylvania, USA, had it built.

Transporting stone from quarry to ship on Portland was never easy.

The right quantity of stone had to be delivered to the piers and it had to be ensured that men were available to use carts or 'plows' to carry the stone to the harbour - and they sometimes had other priorities.

Storms and major landslips at the stone piers also created problems.

Next week we look at the building of museums in London in the 1800s and the building of grand landmarks as the British Empire grew.

'Stone to Build London' is available from Folly Books for £24.99 with free postage and packaging.

See follybooks.co.uk or call 01225 859689.

CONTACT ME:

t: 01305 830973

e: joanna.davis

@dorsetecho.co.uk

Twitter: @Dorset EchoJo

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here