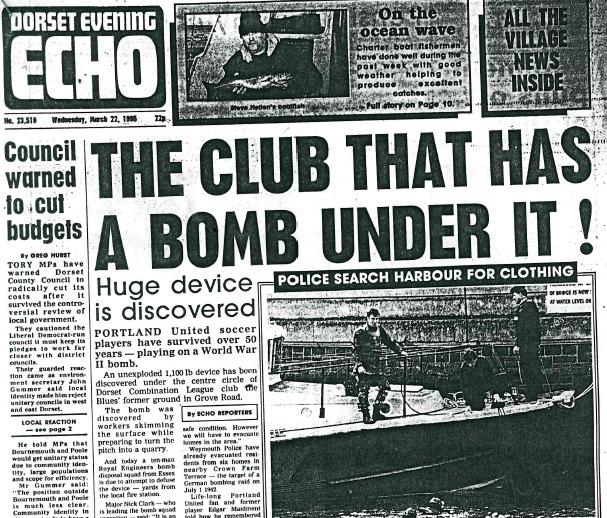

In 1995, an unexpected discovery on Portland thrust the small island into the national spotlight, when an unexploded bomb was found beneath the old football pitch on Grove Road. More than 24 years later, we look back on the event that led to one of the biggest peacetime evacuations in Britain's history.

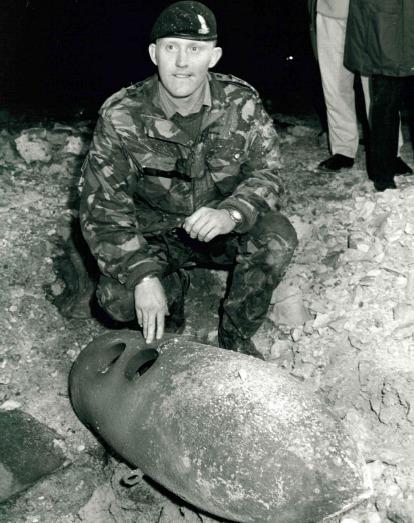

On Wednesday, March 22, 1995, the Dorset Evening Echo reported that workers preparing to turn the pitch into a quarry had discovered a 1,100lb bomb buried beneath the centre circle of the Blues' former ground. It dated back to the German bombing of Crown Farm Terrace, which took place during the Second World War on July 1, 1942.

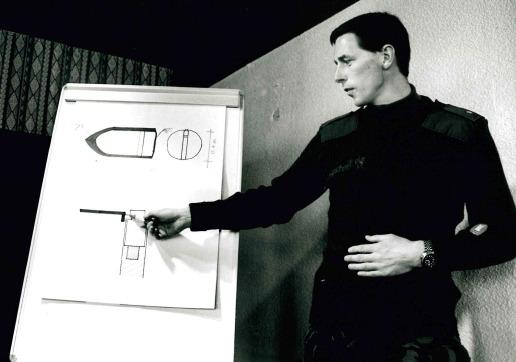

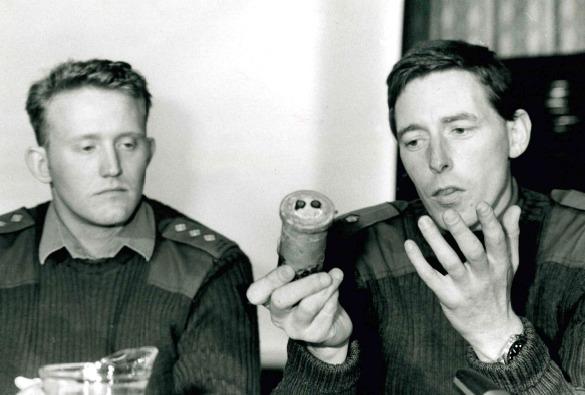

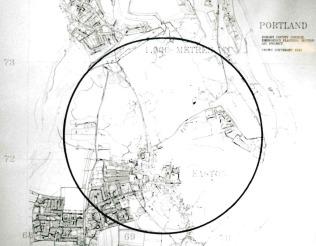

The discovery was followed by the planned evacuation of more than 4,000 residents from within a 1,000 metre radius of the device, and the arrival of a 10-man Royal Engineers bomb disposal squad from Essex.

Dubbed Operation Seabird, the evacuation was far from without its challenges. There was staunch opposition among residents who attended public meetings in their hundreds, voicing concerns about looting, loss of business and leaving their pets behind.

A spokesman for Dorset Police, Mike Maber, responded, saying that the force was in contact with animal organisations including the RSPCA. He urged people to take valuable belongings with them and stressed that police would be on patrol to ensure there was no looting in the area.

Still, problems remained. There was the question of whether to evacuate the 350 inmates and 120 staff from the Young Offenders Institution, which was situated on the border of the 1,000 metre zone. Certain residents seemed particularly reluctant to leave, claiming the compulsory evacuation was an infringement on their democratic rights.

One such resident was island historian Edward Andrews who, aged 81, had spent 17 years in the Territorial Army and another 35 working in Portland's prisons.

"They wanted to forcibly remove us from her homes," Edward said. "The army said they would not act until everyone was removed. It was emotional blackmail."

He added: "The one kilometre exclusion zone was total nonsense. A blast loses its power very quickly; there would have been more danger on St Mary Street in Weymouth on a Saturday afternoon."

However, by the day of the evacuation - April 1 - only a handful of dissenters remained, officially recorded as nine people from five houses.

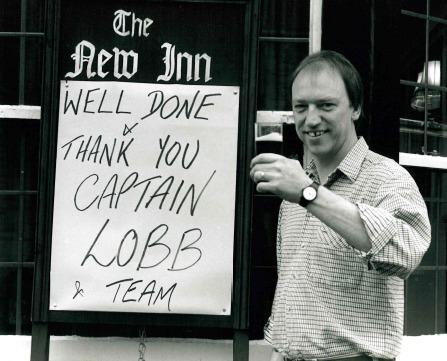

Captain Mike Lobb, then 26, was entrusted with the nail-baiting task of defusing the bomb. Speaking to reporters a decade after the event, he humbly declared: "At the end of the day I was just doing my job. I knew I had the right training, so if the bomb blew up it was probably my own fault. It would have happened in seconds and I probably wouldn't have known much about it anyway." Mike also stated that the evacuation was "completely necessary" given that "a bomb of that size will shower shrapnel through the air for some considerable distance."

Despite a 12-year stint in the army, Mike described the incident as the highlight of his career. "I have a huge affinity with Portland because they looked after me so well," he said. "It was humbling to be taken in and welcomed by people I was putting out."

Yet even after the bomb was safely defused and the residents of Portland settled back into their houses, the consequences of the discovery were far from over. In an unprecedented move, members of the parent-teacher association at Royal Manor Comprehensive School demanded compensation from the German embassy after their fun day, scheduled for April 1, had to be called off. PTA spokesman Peter Norster was reported saying: "Going on the figures from previous years we stand to lose £3,000 because of the bomb. I have sent a letter to the German embassy claiming compensation because it was the Germans who dropped the bomb in the first place."

The Germans retaliated with the statement that the school should seek compensation from British Army, as it was they who had chosen that particular day to defuse the bomb. Spokesman Peter Gottwald added: "Unexploded bombs are found in Germany all the time but we don't hear of people looking for compensation."

The operation is thought to have cost the borough council and police force an estimated total of £200,000, much of which was eventually reimbursed by the government.

Although the evacuation was praised for the quality of its planning and coordination, confidential documents later released under a Freedom of Information request showed that it had been hampered by temperamental computer systems, an unexpected number of pets and unsuitable accommodation for vulnerable people. Social services were said to have born the brunt of the difficulties imposed by moving thousands of people from their homes, while the reports also revealed that counselling was offered to council staff because some of them found the work distressing.

Regardless, the fact that footballers from Portland United played mere metres above the bomb for more than 50 years is remarkable, and both the work of the town's authorities and the bravery of the bomb disposal team is admirable.

In a final twist, it later emerged that the quarrymen were in fact not the first to detect the ton of explosives lying just beneath the pitch's surface. Comet, an eight-year-old explosives sniffer dog, was taking part in a dog handling display when he picked up the scent, running straight to the centre line and indicating a find.

Norman Pearce, who had organised the display, commented: "Comet's behaviour baffled us all. We realised later he had found over a ton of TNT, but at the time we couldn't think what was wrong. Who would think there would be a bomb under a football pitch!"

These days, the bomb, which caused such a massive stir more than two decades ago, is on show in the gardens of Portland Museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here