Today we relive a fascinating account of one man's life and times in south Dorset during the First World War and in the 1920s and 30s.

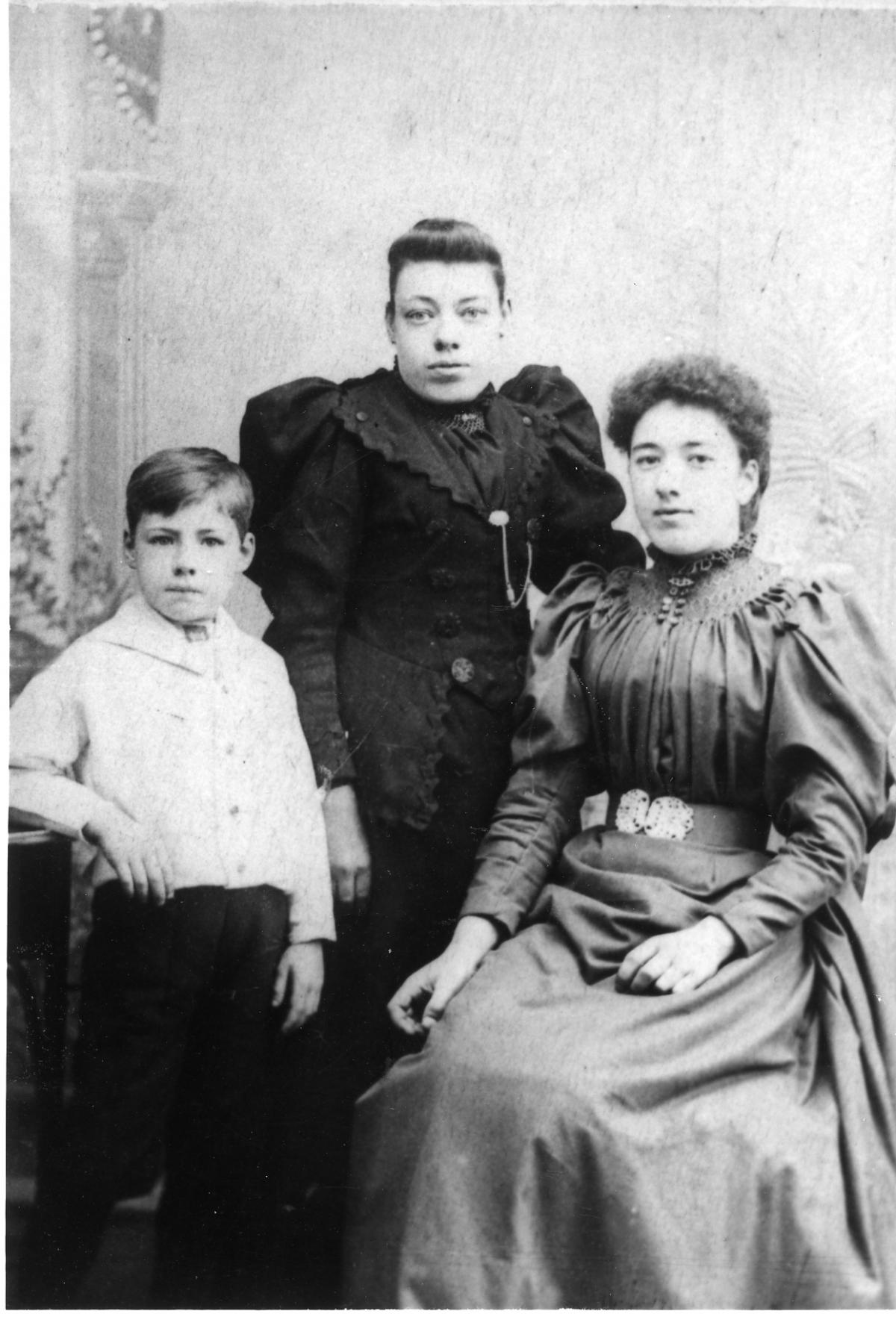

The late Herbert William Bird was born in Islington in 1912 and spent his childhood years in Chickerell.

He died in 2004 but his memories live on in 13 volumes of his autobiography. They have been kept in perfect order in red folders that were passed on to Norman Bennett, founder of the Bennetts Water Gardens in Chickerell, by Herbert's son Michael.

Norman said that he found the writing fascinating as it reflected his own interests and memories of growing up in the Suffolk countryside.

"Farming then was completely different, like that woman who walked seven miles there and back just to sell a few eggs. That was a common occurrence, it was like a different world. Being 85 I remember from the age of about four or five these conditions in the depths of Suffolk.

"Although Herbert was born in London in 1912, at the age of five he was sent to live with his aunt Em, Mrs Ernest Butler at Sea Barn Farm at Fleet in Chickerell.

"The autobiography gives an accurate and interesting insight into country life in south Dorset during the First World War and in the 1920s and 30s."

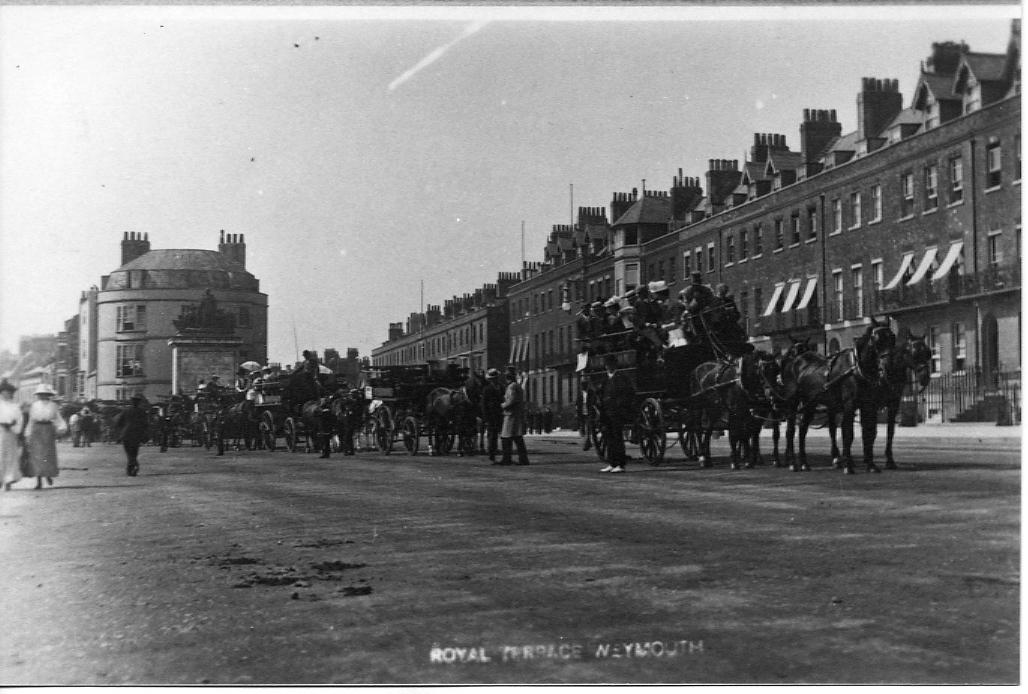

Herbert clearly remembered his time in Chickerell, and later in Weymouth, fondly. From the first page he speaks of how it holds the fondest place in his memories and throughout the first three volumes he regales the pages with recollections of an age long gone.

Here is an instalment of his writing about swapping the city for a life in country.

On page three of the first instalment he wrote: "But my most pleasurable memories of those bygone years are of my stays with the most liveable couple I had ever known - my aunt and uncle at Fleet in Dorset. I was sent down there when the Germans started to drop bombs with some regularity over London. How insignificant their efforts now seem after experiencing over five years of firefighting in the Second World War.

"I was put in the guards van at Waterloo Station with the rest of the paraphernalia for despatch, by my mother, and I still recall that I was so shy that piddled myself on the way down because I was too afraid to ask the guard to take me to the toilet. I was met at Weymouth station by my Aunt Em and recognised her straight away - or so I thought. She too was amazed that as she hadn't seen me since I was a babe in arms, and must have thought "we've got a right one here".

"It was only after I had asked how Albert and George were that she cottoned on to the fact that I had mistaken her of my Aunt Ada who lived at Bromley in Kent and who I had seen quite often.

"I stayed with them at Sea Barn, an old stone built cottage on the back water of the Chesil Beach for nearly a year, going to the local school at Fleet which consisted of one teacher and about 16 or 17 children from my age up to 14.

"That old mistress must have been something out of the ordinary, for despite all the obvious drawbacks, plus having pupils whose parents in quite a few cases could barely read or write properly many of those children have done very well for themselves.

"One day I hope to go back there and have a look round at old Fleet and see how much is still as it was. I understand the remains of the of church and vaults used by the smugglers in the olden days are still to be seen."

Herbert went on to describe his return to London "full of so many 'be's' and 'I's' that for weeks my mother could hardly understand me".

When he was nine years old Herbert came back to Weymouth for 11 months, this time to Moor Farm off Abbotsbury Road as his aunt Em and Uncle Ern had moved.

He wrote: "This was a delightful old farm and it was here that I saw growing for the first time medlars, and to this very day I'm not certain whether I like them or not, but to be sure I could very well live without them. At the rear, and completely covering that side of the house was a beautiful blush rose, which I think must have been the old climber called the Seven Sisters for I can find no other in any of my rose books which resembles it.

"This time I went to school in Chickerell and the children there gave me hell for the first few months, the 'townie' was the butt for everything going, and believe me 'going' was the operative word if one wished to stay in one piece. Speed was essential in those days, and with about a dozen and a half boys after you every time you left the safety of the school it was no wonder I developed into the best runner they had.

"After a few months I was reprieved, another foreigner had arrived at the school and almost overnight I was accepted as part of the village life and the other poor devil took over rather unwillingly as the butt of their enthusiasm to catch and destroy.

"By this time I had been given the nickname of Eagle, only partly in reference to my surname but mostly because of my fleetness in escaping their grasping hands and the habit I had acquired of hiding when chased and then pouncing on any old stragglers of the pack of hounds pursuing me, giving him a doughboy and beating it again before his shouts for assistance brought the main pack back on my heels again.

"A very large field close to the school known locally as the fuzzy ground was my favourite haunt and ideal for these tactics, being overgrown with gorse and bramble."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel