IT was interesting to come across an article written in 1916 and published in 1917 looking at poverty in Dorset 70 years previously - in 1846.

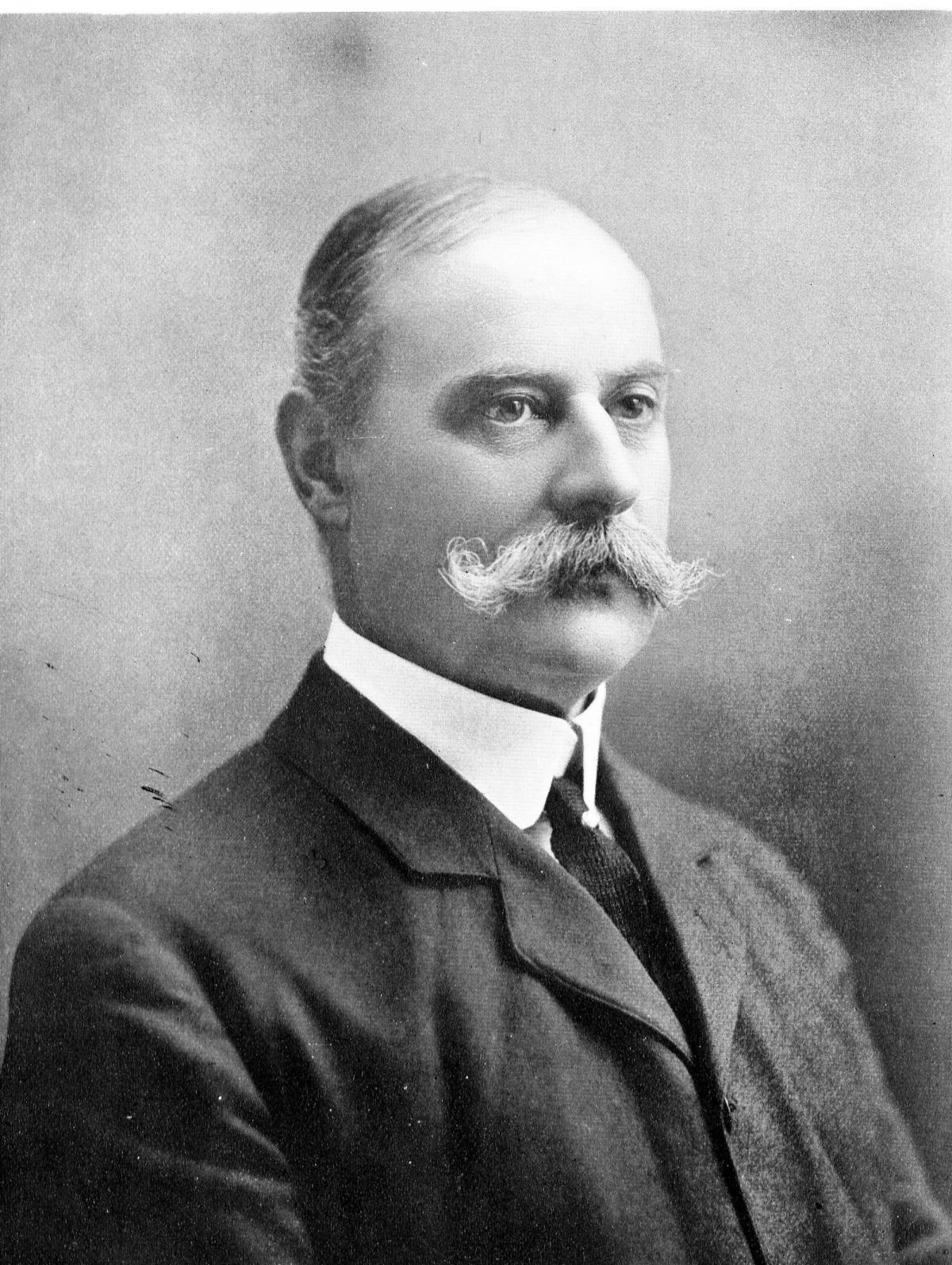

The piece was written by Dorchester man Sir Frederick Treves, who gained fame as the man who looked after the Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick and was also known as the Royal surgeon to Edward VII, operating on his appendix and saving his life just two days before the planned date of the King’s coronation.

In the article, which was published in the 1917 Annual Year Book of the Society of Dorset Men, Sir Frederick refers to a piece in the Times on Dorset farm labourers.

Our thanks to Roger Lane of West Stafford near Dorchester who submitted this 1917-published article and has enabled us to delve into what life was like for 'peasants' of the county.

The article tells us that a debate in the House of Commons told people that the condition of peasantry in Dorset was little better than that of their fellows in Ireland, except that people were not lacking in potatoes.

Sir Frederick writes that Dorset's comparison to Ireland was not credited and 'readers of journals, lolling in the clubs, pooh-pooed and pshawed and sent for maps to see where Dorset was.'

The editor of the Times dispatched a commissioner to the county, we are told, 'to report upon the condition of peasantry'. An artist was sent from the Illustrated London News to make sketches from the life of the Dorset labourer and of 'his native haunts'.

The artist arrived in East Morden near Bloxworth to make sketches. He found that all the cottages were thatched and 'the roofs were not always impermeable to rain, while the walls were often so cracked that the wind could only be kept out by a stuffing of rags.'

"The cottages are built with mud walls, composed of road scrapings, chalk and straw; the foundation is of stone or brick, and on this the mud wall is built in regular layers, each of which is allowed to dry and harden before another is put over it."

Sir Frederick notes that the artist noticed, as a rare curiosity, that the garden walls were also of mud and they, like the cottages were also thatched,

Other observations were that cottages were supported by props for keeping falling walls together, floors inside were made of mud and a 'heap of squalid half-clothed children rolling upon it' could be seen inside. Some of the cottages were described as almost in ruins while others were little better than hovels.

People would get to their bedroom by climbing up a ladder. Many windows had no glass and opening were stuffed with rugs. In one room occupied by a family of eight there were two tables, one chair and a 'rude bench' 4ft long. The cradle was of rough boards clumsily nailed together.

When the Times correspondent visited Hilton, near Milton Abbas, he found that the bed clothes were rags, while the bed and pillows were stuffed with 'oat-dust' swept off the barn floor.

Wages paid throughout the county varied from seven to eight shillings a week and for this the labourer worked 12 hours a day. This represented a fraction over one penny farthing per hour. And from these meagre wages a sum would be deducted for rent. In some places the deduction was sixpence a week, while in a few favoured districts the labourer - especially if a carter of a shepherd - lived rent free.

Sir Frederick goes on to compare the state of Dorset labourers to slaves - "Considering that the Act for the Abolition of Slavery in the British Colonies was passed in 1833, it is astounding that it was only an accidental enquiry in 1846 that revealed the desperate state of those who laboured on the rich farm lands of Dorset and whose conditions was, in many respects, infinitely worse than that of the West Indian slave."

Other curious features noted in Dorset were that an unmarried man was regarded as 'a boy' and was paid as a boy at the rate of five to six shillings a week. Labourers who became too old to work or whose prospects were not encouraging had the poorhouse to look forward to. There was one at Yetminster which was described as 'as complete a scene of wretchedness as the county is capable of producing.'

Despite the hardship, the Times correspondent found the Dorset farm labourer to be 'patient and uncomplaining and actually cheerful'.

"He faced his position with that courage and determination which have ever been characteristic of the Dorset people and with a lightness of heart which no hardship could dismay."

Sir Frederick goes on to mention that the labour movement, then prominent in 1916, had hardly made its existence felt in 1846. He writes of the Tolpuddle Martyrs and remarks that in the 'three score years and ten that mark the span of a human life', progress accomplished within that period was 'astounding'.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here