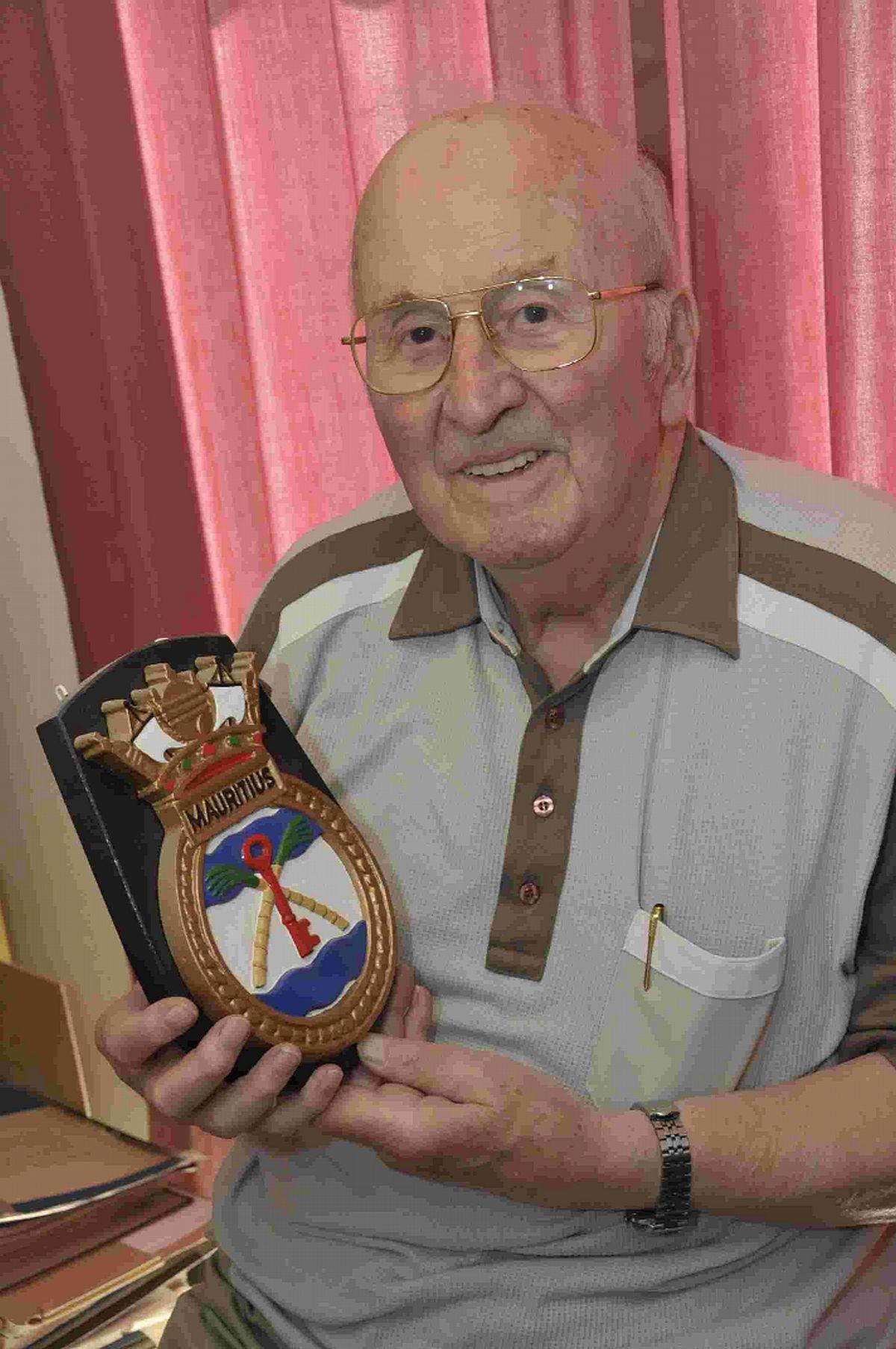

Eric Alley served in some of the most iconic operations of the Second World War, including the D-Day landings and the Arctic Convoys to Russia, for which he successfully campaigned for a commemorative medal.

Eric Edward Alley, OBE, died on May 17 last year days before he was due to receive the honour he had campaigned for.

As a radar operator Mr Alley served on board the HMS Mauritius off the beaches of Normandy in June 1944. His role was to keep a look-out for small ships, aircraft and E-boats attempting to attack his vessel – and to plot the distances to the German targets on the French coast five miles away.

In this personal account of his service that day, Mr Alley, of Weymouth, describes the pounding the Mauritius inflicted on the Germans’ defences and the gratitude of his superiors for a job well done.

“I don’t think enough is known about the decisive part played by naval gunnery in the battles around Caen and for that matter throughout the Normandy campaign.

“The use of the warship in direct tactical support of land troops is really an astonishing thing.

“HMS Mauritius, a six-inch gun cruiser, had an almost unique experience.

“She was engaged in every landing from the Mediterranean to Normandy and fired a record number of rounds for her class – upwards of 9,000.

“This is far more than was fired by any warship during the whole of the First World War campaigns that took place between 1914 and 1918.

“The battery the Mauritius carried was a formidable affair, having four turrets, each equipped with three six-inch guns with a top rate of fire of nine rounds per minute.

“What this means, I think can be best realised by a comparison.

“In a given period, HMS Mauritius could smother a target with a weight of explosives very considerably more than could be fired by two complete regiments of field artillery.

“But weight is one thing, precision is another. And the precision of this ship’s shooting is amply borne out by her logbook.

“I remember a collection of the signals sent to her either from the Observation Post or from the Commander of the land forces engaged.

“They were extremely satisfactory – ‘Good shooting’, ‘Many hits, many thanks’ and ‘Commanding Officer’s thanks, best shooting we’ve had yet’.

“One of the signals I like best referred to a target where the enemy was reported to be massing for an attack.

“After a quick shoot back came the signal ‘Enemy discouraged’ – a pleasant British understatement.

“And there was another even more laconic – the sole acknowledgement in this case was a single word: ‘Beautiful’.

“I like to remember ‘beautiful’ being breathed over the ship’s loudspeaker to the waiting gun detachments, in addition to all those members of the ship’s company, who could not see the action.

“But what brought about the new effectiveness of ships’ guns in the land battle?

“I was not a gunner so I cannot go into technical details but I think it would be agreed that the improvement was above all due to two things.

“Firstly, the use of thoroughly trained observers on the ground and in the air, and, secondly, the way the results of observation became instantly available by radio and WT.

“Every gunner knows that nothing can really take the place of exact observation of the fall of shell but the great forward strides that made in systems of communication meant that the observing officer, whether he was sitting in a ditch or watching overhead from a Spitfire or a Piper Cub could signal the result straight back to the gun control position on the ship, itself.

“Of course there were other factors, including the, then, amazing miracles of computation performed in the Transmission Station in the bowels of the ship.

“It was there you had the uncanny machine that solved all the problems set by a moving gun platform.

“The effect on the shell, of wind, of barometric pressure, of the movement of the ship, deflections and variations of all sorts – unseen antennae conveyed these data to the machine – and out came the answer. And then, swifter than any verbal orders, the circle was completed through the transmitter, director, gun control and turret. But the machine was nothing without the men.

“My shipmates on board the Mauritius were a young lot. The Royal Navy made us her own – and we were never more the stuff of the Royal Navy than when we were under fire.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here