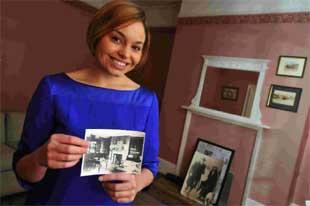

SELF-CONFESSED Anglophile Jacqueline Dillion couldn’t have found a better base to write her PHD on Hardy’s literature.

The American student was taken by surprise when the previous tenants of Max Gate in Dorchester – the house that Hardy designed, built and lived in for more than 40 years – asked her to move in.

Jacqueline told how she came to the county town to feel ‘more connected to the world of Hardy’ but that she wouldn’t have even dreamed about living in the house where Hardy played host to the luminaries of his time including Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson and H G Wells.

The 28-year-old, whose smile widens every time she mentions Hardy, said she was on the hunt for a small cottage when the former custodians Andrew and Marilyn Leah – whom she knew through the Thomas Hardy Society – asked if she would like to take on the imposing brick home.

Before long Jacqueline and the Leahs were drinking cider and listening to folk music around a fire at Hardy’s birthplace, the cottage at Higher Bockhampton, in celebration of the National Trust, which owns both properties, approving the move.

Jacqueline, who was a former military intelligence specialist in the US Army, told how she kept a dirty copy of Tess of the d’Urbervilles under the seat of the Humvee in Baghdad.

Jacqueline grew up in a rural part of Arkansas in the USA but always longed to move to London – and later to Dorset.

She said: “I’m an Anglophile – I always wanted to move to the UK because I love everything English.

“I grew up reading Thomas Hardy and all the English classics and I was just fascinated by the history here – there’s a real sense of past.

“My dream was always to get to London, but being in London I felt a little bit out of the Hardy loop.

“I thought I could be much more involved with him and the world of Dorset and the world of Hardy if I moved here. I just felt I needed to get here so to be asked to live at Max Gate was such a surprise – I feel incredibly privileged.”

Ms Dillion, who discovered Hardy’s work at the tender age of 14, added that she felt a distinct presence of Hardy at Max Gate.

She said: “Hardy wrote about people who were living in Dorset, so being here you really get a sense of Hardy and the people he was writing about. He wrote about people that are often taken for granted – if Hardy wasn’t going to write about them, Dickens wasn’t going to, Jane Austin wasn’t going to.

“Hardy was looking to preserve the lives that wouldn’t normally be written about and that’s important.

“I definitely feel connected to Hardy being here.”

Jacqueline is writing her PHD in the very study in that Hardy composed The Mayor of Casterbridge and The Woodlanders.

The former frontline solider seems to be adapting perfectly to the huge Victorian house that she described as ‘peaceful’ and ‘calming’ – a place where she could ‘really think’.

From a battered book of Hardy’s work full of post-it notes on the desk, to the guitar propped up against the wall to represent Hardy’s love for music, many additions to Hardy’s former study evoke a presence of the English novelist and poet.

The room wasn’t Hardy’s study forever though, despite it being built for that purpose. Jacqueline said that when he became estranged from Emma, the first of his two wives who eventually retreated to the attic, he moved out of their bedroom and into the study, using a much smaller and inferior room to write in.

She said: “Hardy would barricade himself in his study and they became estranged in this house, drifting further and further apart. He ended up moving out of the bedroom they shared together – he said he needed his own space.

“Eventually she lived up in the attic by herself.”

Jacqueline said that while Emma, who was from Cornwall, hated Dorset, his second wife Florence, who was from Enfield, hated the house.

She said: “Emma hated Dorset because it wasn’t Cornwall, it wasn’t where her family were and she didn’t know anyone.

“Florence wasn’t worried about Dorset, but she hated the house.

“Maybe he needed a good Dorset woman. Dorset was everything to Hardy.”

Hardy died in Max Gate in 1928 and in 1940 Hardy’s sister left the house to the National Trust with the stipulation that it should be lived in. Though Max Gate has been continually occupied since then it was first open to the public in 1994 where the hall, dining room and drawing rooms and gardens have been open twice a week.

A National Trust spokesman said that the opening arrangements for this year had not yet been decided.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel