THE horrors of war have been documented in the First World War diary of an ambulance worker.

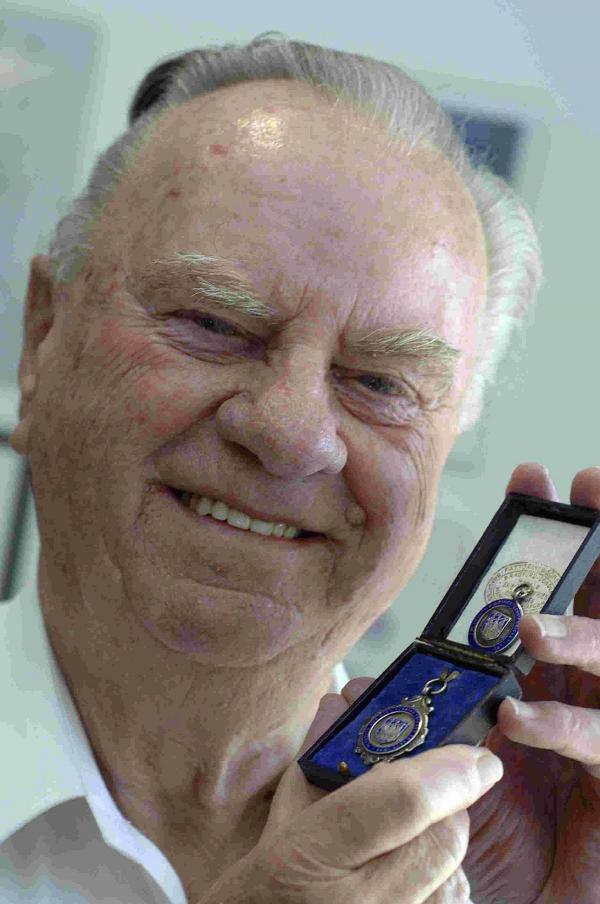

Portland resident Jack Sansom was given his uncle’s diary following his death in 1978.

Jack put the notebook away in storage for years and has recently starting re-reading it.

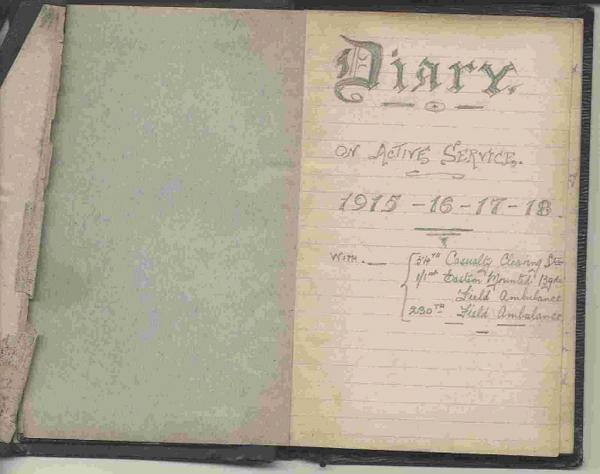

The diary, yellowing around the edges but in pristine condition, tells of James Sansom’s harrowing experiences as a stretcher-bearer working for the Field Ambulance close to combat zones.

James, who was born on Portland, kept the diary between 1915 and 1918.

The powerful and moving diary entries tell of the hardships of war – carrying wounded soldiers, the scarcity of food and water and the shock of seeing men reduced to skeletons.

Tucked inside the diary is a book ‘Words of Comfort and Consolation’, containing prayers to provide solace for soldiers.

Jack said: “There aren’t too many First World War diaries around so I think this diary is very interesting.

“His writing is very humble and he hasn’t made anything sound disastrous.”

This is particularly noticeable when James writes about digging the graves of those killed near Gaza.

On April 14, 1917, he writes: “We get our first experience of bombing and about 10am Johnny Turk shells for three hours causing about 80 casualties, including 14 killed, all belonging to the Royal Army Medical Corp. I help dig graves in the afternoon.”

The diary begins in January 1915 when James went to Weymouth to enlist. By January 12 he had left Portland for Aldershot and then to Wales for training.

The diary mostly tells of the former quarryman’s involvement in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign.

On April 17, 1917, he writes: “We move again at night to a position near the front line where there is a terrific bombardment on and we have a tremendous lot of casualties to handle.

“We stay here all night but don’t get any rest. We are short of water too and it is very hot all the while.”

James writes how the water shortage causes hundreds of men in the unit to be suffering from heat stroke and extreme exhaustion.

In November, James is on the move once again with the medical unit sleeping near captured trenches and passing an enemy aeroplane which was brought down.

“It is very hot and we are very short of water so we aren’t very happy and to add to our troubles we get shelled and also bombed by low-flying planes.

“I think this is about the ‘happiest’ Sunday I have had up to the present. However, we only have three casualties.”

The medic again shows his dry sense of humour when he explains what happened on November 5, Guy Fawkes Day.

“We get a decent display today from ‘Johnny’ after we get a new position,” he writes.

James continues to tell how the men have been unable to wash or shave for 12 days.

“We all look very rough,” he writes.

“We get a bath and a good shave and of course we are all infested with lice, officers and all.”

He then tells of a 3am attack in the pitch black in the Vale of Ajalon.

“We are heavily shelled and we get a tremendous amount of work as there are many casualties. It has been raining for two days and the rough paths are in a mess.

“We have to carry the wounded back to the monastery a distance of four miles and most of the road is under shell fire.

“We work continuously for 40 hours with only a mug of tea occasionally to keep us going.”

The horrors of war continue, as James writes on December 12, 1917: “We advance with the infantry and some of our fellows have to carry the wounded eight or ten miles by hand as it is still too wet for camels.

“It rains continuously over this period and we go short of rations in consequence of the roads which were too bad for transport.”

He spends Christmas Day at a service in a monastery with an impromptu concert at night, without much in the way of ‘grub’.

On December 31, James writes: “We get a lot of wounded and sick prisoners in today and also some of our men who had been in Turkish hands.

“They were all mere skeletons and we found a lot of them to be suffering from typhus. Many of them die, some of our men get infected with typhus as well.”

In 1918, James’ unit is moved to northern France and then he gets 14 days’ leave to go home to England.

“I’m not feeling very jolly until I reach the unit once again on July 29,” he writes.

The diary ends in December 1918, when James is staying in Brussels. His situation has much improved, he writes: “We are billeted in a water mill while we have our hospital in the village school.

“We are having an easy time now, no parades, get up what time we please and the people are very good to us. We have several concerts and have a good time generally at Christmas, plenty to eat and drink for those that liked it.”

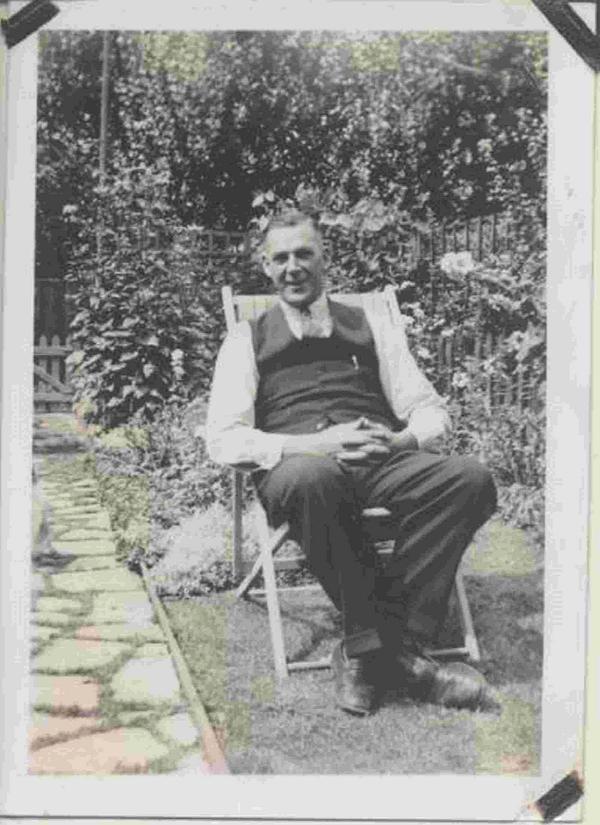

When he returned from the war, James made his home in Henley-on-Thames and joined the Metropolitan Police.

He married Elsie after the war and spent holidays on Portland.

Jack, who used to run the Red Triangle Cricket Club, said: “My uncle used to come down and holiday and tutored me for cricket and tennis.

“I think it’s fantastic that someone in the war could keep a diary on all the activities he did.

“I’ve known it was there for years but I put it away, I thought now was the right time to bring it out and look at it again for the centenary of the start of the First World War. It’s a story that should be shared.”

James Sansom died in 1978 aged 83.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article